In the cities of ancient Russia, workshops differed from ordinary buildings in that the furnace was located not in the corner, but in the middle (they find production waste, semi-finished products, and sometimes tools). One of the most respected and early emerging crafts was ironworking. Domnitsa, where iron was smelted, was moved outside the city, which was determined not only by fire-fighting measures, but also by the proximity of raw materials: surface deposits of marsh and meadow ores were used to obtain iron. Within the city walls were mainly blacksmith workshops. Blacksmiths received iron in the form of krits (semi-finished products). They were forged to obtain pure metal. The variety of ferrous metal products is extremely large - from the simplest nails and staples to complex weapons.

Medieval blacksmiths were familiar with several grades of steel obtained by repeated forging forging or aging (languishing) in an earthen vessel in a furnace. The blacksmith's tools were distinguished by rationality - the forms of these things have not changed even now. All kinds of forging products required knowledge and application of various processing technologies. Moreover, each land used its own methods. So, in the north of Russia until the middle of the XII century. there was labor-intensive strip welding of steel and iron, which made it possible to create self-sharpening blades. Later, the technique was simplified to welding a steel strip onto an iron base. The demand for blacksmith products and the development of craftsmanship in the XII century. led to the allocation of various blacksmith specialties among urban artisans. According to written sources, armorers (gunsmiths), cutlers, locksmiths and others are known.

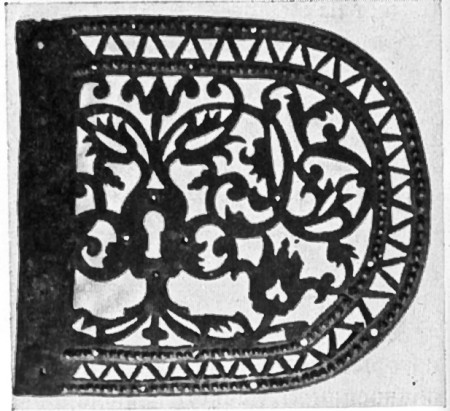

Products of Russian blacksmiths were also valued in other countries. It is no coincidence that in the Baltic States, the Czech Republic, and the Balkans, ordinary objects are found, such as padlocks and keys made in Russia. The lock was made like this: a spring was inserted into the cylindrical case, which was one or two thin plates soldered onto the rod. The second end of the spring rod was fixed in a small cylinder connected to the first plate. At the bottom of the large cylinder was a key hole. What could be easier? But it is enough to change the thickness or number of plates in the spring - and another key is needed. That is, each lock and key to it were single. It is not surprising that locksmiths emerged early as a separate specialty, because the lock had from 35 to 42 parts assembled by soldering. The body of the castle, as a rule, was decorated with overlaid parts made of copper alloys or completely covered with non-ferrous metal.

Non-ferrous metals were used quite widely, and their processing methods were common: casting, forging, stamping, embossing, embossing. Raw materials were either brought, often from afar (Scandinavia, Hungary), or often smelted from old or broken things. Craftsmen's products made of non-ferrous metals were in great demand: a variety of women's jewelry, costume details and accessories, religious objects and church utensils, weight weights, flails and maces for soldiers. By the middle of the XII century. along with other technologies, they invented casting in imitation forms, which made it possible to reproduce complex jewelry from a cheap lead-tin alloy. Such "splash" casting - the metal poured into the mold solidified on its walls with a thin layer, and the excess splashed out - made it possible to obtain hollow light decorations, and rare metal was saved.

"Copper smiths" were made in the XII-XIII centuries. decorations for both townspeople and residents of the district. They also made cult objects: cross-vests and encolpions, church decoration and utensils. One of the most impressive examples of such products are the arches from the church of the Vshchizh settlement (in the 12th-13th centuries it was a real city, its ruins were discovered at the end of the 19th century on the territory of the Bryansk region). They are cast using the wax model technique, that is, with the loss of shape. The openwork belt ornament is divided by ovals with images of heraldic birds. These arches are valuable not only for the elegance of execution, but above all for the master's signature, which was added during casting: "Lord, help your servant Konstantin." This is the rarest case, since almost all medieval art is anonymous. Among several dozens of epigraphic monuments, a few names of masters were found. Most often they are found on church objects. The exception was a jeweler named Maxim, who marked his casting molds, one of which was found in Kiev, and the second in the center of metallurgists - Serensk (the city was burned down during the Mongol-Tatar invasion; now the village of the same name in the Kaluga region stands in its place).

In Russia, iron was known to the early Slavs. Most old method metalworking is forging. At first, ancient people beat spongy iron with mallets in a cold state in order to "squeeze the juice out of it", i.e. remove impurities. Then they began to heat the metal and give it the desired shape.

Already in the 7th-9th centuries. the Slavs have special settlements of metallurgists. Forges in Slavic settlements were located away from residential buildings, near rivers: the blacksmith constantly needed fire in the forge to soften the metal and water to cool the finished products. Blacksmithing was considered by the Slavs to be a mysterious and even witchcraft occupation. No wonder the very word "blacksmith" is related to the word "intrigues". The blacksmith, like the plowman, was a beloved hero of Slavic folklore.

In the products of the ancient Slavs, the ornament is very calm, and the images do not inspire fear in a person. Inhabitant of the endless wilds, ancient slav saw in fantastic creatures that inhabited, as he believed, forests, waters and swamps, not so much his enemies as patrons. They protected and protected him. He felt involved in their lives, and therefore in art, in forged products, he sought to emphasize this indissoluble bond. The artistic tastes and skills that formed then did not disappear with the rise of feudalism and the adoption of Christianity.

The process of feudalization led to the formation in the 9th century. Kievan Rus, a large state that quickly gained fame throughout the then world.

The name of the legendary founder of the city of Kiev - Kiy - is related to the word "forge"; the name itself could mean "club", "hammer". In Ukraine, legends are known about how a blacksmith harnessed a monstrous snake to a plow and forced it to plow furrows that became riverbeds or were preserved in the form of ancient fortifications - “serpent shafts”. In these legends, the blacksmith is not only the creator of handicraft tools, but also the creator of the surrounding world, the natural landscape.

The complexity of the process singled out blacksmiths from the community and made them the first artisans. In ancient times, blacksmiths themselves smelted the metal and then forged it. The necessary accessories of a blacksmith - a forge (smelting furnace) for heating a cracker, a poker, a crowbar (pick), an iron shovel, an anvil, a hammer (sledgehammer), a variety of tongs for extracting red-hot iron from the furnace and working with it - this is a set of tools necessary for melting and forging works.

For Kievan Rus, the adoption of Christianity was of progressive importance. It contributed to a more organic and deeper assimilation of all the best that Byzantium, which was advanced for that time, had.

In the X-XI centuries, thanks to the development of metallurgy and other crafts, the Slavs had a plow and a plow with an iron plowshare. On the territory of ancient Kiev, archaeologists find sickles, door locks and other things made by the hands of blacksmiths, gunsmiths and jewelers.

In the 10th century, above-ground stoves appeared, the air was pumped into them with the help of leather bellows. The furs were inflated by hand. And this work made the cooking process very difficult. Archaeologists still find signs of local metal production on the settlements - waste from the cheese-making process in the form of slag.

In the 11th century, metallurgical production was already widespread both in the city and in the countryside. The raw material for obtaining iron was swamp and lake ores, which did not require complex technology for processing and were widespread in the forest-steppe. The Russian principalities were located in the zone of ore deposits, and blacksmiths were almost everywhere provided with raw materials.

Very quickly the culture of Kievan Rus reached high level, competing with culture not only Western Europe but also Byzantium. Kiev, one of the largest and richest cities in Europe in the 11th-12th centuries, experienced a brilliant heyday. According to Titmar of Merseburg, a German writer of the early 11th century, there were several hundred churches and many markets in Kiev, which indicates a brisk trade and vigorous building activity. The applied art of Kievan Rus, the art of blacksmiths, was distinguished by high skill. Having gained distribution in everyday life, it equally manifested itself in cult objects (salaries, carved icons, folding crosses, church utensils, etc.).

Written sources have not preserved to us the forging technique and the basic techniques of ancient Russian blacksmiths. But the study of ancient forged products allows historians to say that the ancient Russian blacksmiths knew all the most important techniques: welding, punching holes, torsion, riveting plates, welding steel blades and hardening steel. In each forge, as a rule, two blacksmiths worked - a master and an assistant. In the XI-XIII centuries. the foundry partly became isolated, and the blacksmiths took up the direct forging of iron products. In Ancient Russia, any metal worker was called a blacksmith: "blacksmith of iron", "blacksmith of copper", "blacksmith of silver".

The simplest forged products include: knives, hoops and buds for tubs, nails, sickles, braids, chisels, awls, shovels and pans, i.e. items that do not require special techniques. Any blacksmith alone could make them. More complex forged products: chains, door breaks, iron rings from belts and harnesses, bits, lighters, spears - already required welding, which was carried out by experienced blacksmiths with the help of assistants.

The production of weapons and military armor was especially developed. Swords and battle axes, quivers with arrows, sabers and knives, chain mail, helmets and shields were produced by master gunsmiths. The manufacture of weapons and armor was associated with especially careful metal processing, requiring skillful work techniques. Russian helmets-shishaks were riveted from iron wedge-shaped strips. The well-known helmet of Yaroslav Vsevolodovich, thrown by him on the battlefield of Lipetsk in 1216, belongs to this type of helmet. It is an excellent example of Russian weapons and jewelry of the XII-XIII centuries.

In the XI-XIII centuries, urban craftsmen worked for a wide market, i.e. production is on the rise.

In the XIII century, a number of new craft centers were created with their own characteristics in technology and style. But we do not observe any decline in the craft from the second half of the 12th century, as it is sometimes asserted, either in Kiev or in other places. On the contrary, culture grows, covering new areas and inventing new techniques. In the second half of the 12th century and in the 13th century, despite the unfavorable conditions of feudal fragmentation, Russian craft reached the most complete technical and artistic flourishing. The development of feudal relations and feudal ownership of land in the XII - the first half of the XIII century. caused a change in the form of the political system, which found its expression in feudal fragmentation, i.e. creation of relatively independent states-principalities. During this period, blacksmithing, plumbing and weapons, forging and stamping continued to develop in all principalities. In rich farms, more and more plows with iron shares began to appear. Masters are looking for new ways of working. Novgorod gunsmiths in the 12th - 13th centuries, using new technology, began to produce blades of sabers of much greater strength, hardness and flexibility.

In the architecture of Ukraine 14-17 centuries. Fortress architecture was of great importance. The territory of Ukraine then represented the arena of fierce struggle (Poland, Lithuania, Hungary), was subjected to devastating raids of the Tatar and then Turkish hordes. As a result, the products of blacksmiths also served to protect the fatherland, and decorative means were used very restrainedly.

From the middle of the XIII century, the dominion of the Golden Horde was established over Kievan Rus. Events 1237 - 1240 became perhaps the most tragic in the centuries-old history of our people. The cities of the Middle Ages suffered irreparable damage. The craftsmanship accumulated over the centuries was almost lost. After the Mongol conquest, a number of techniques familiar to Kievan Rus disappeared, and archaeologists did not find many objects common to the era preceding the yoke. Because of Tatar-Mongol yoke in the XIII-XV centuries. there has been a significant lag in the development of the cities of feudal Russia from the cities of Western Europe, in which the bourgeois class begins to emerge. A small number of household items of the 14th-15th centuries have survived to our time, but even they make it possible to judge how the development of crafts in Russia gradually resumed. From the middle of the XIV century. a new boom in handicraft production began. At this time, especially in connection with the increased military needs, iron processing became more widespread, the centers of which were Novgorod, Moscow and other Russian cities.

In the second half of the XIV century. For the first time in the country, Russian blacksmiths made forged and riveted cannons. An example of the high technical and artistic skill of Russian gunsmiths is the steel spear of the Tver prince Boris Alexandrovich, which has survived to this day, made in the first half of the 15th century. It is decorated with gilded silver depicting various figures.

From the middle of the 16th century in Ukrainian architecture, the influence of Renaissance art is felt. The influence of northern Italian, German and Polish art is most noticeable in architecture and applied arts cities of Western Ukraine, especially Lviv. The spirit of medieval aloofness and asceticism was replaced by secular aspirations. The motives of nature, inspired by the landscapes of the Carpathian region, are lovingly conveyed in the products of blacksmith masters. The ornament, decoration "vine" has found wide application.

In full force, the artistic features of iron were revealed later, especially in Ukrainian art of the 17th-18th centuries.

Window openings were closed with openwork wrought iron bars, gardens and parks were decorated with skillfully made wrought iron fences and wrought iron gates. Richly decorated iron doors with forging elements decorated stone temples, palaces, in the construction of which masters of all types of crafts took part.

In the 18th century, forging was widely used to make fences for city estates, mansions, and churchyards. The technique of iron casting competes with it, displacing forging as an expensive work. But originality artistic solutions, which is achieved by forging, retains interest in it in the 19th century.

In 1837 A new master plan for Kiev was approved. In 1830-50s. a number of large public and administrative buildings were built in the city: the Institute of Noble Maidens (1838-42 architect V.I. Beretti), the Kiev University Ensemble (1837-43 Beretti), offices (1854-57 M.S. Ikonnikov ). Appeared new type buildings - tenement houses that had floors for shops, a hotel, a restaurant, an office.

The fantasy and skill of blacksmiths, ingenuity, virtuoso mastery of technology, excellent knowledge of the features and capabilities of metal made it possible to create highly artistic works of blacksmithing, an infinitely large and expressive world of forged metal.

The use of forms of various historical styles - Gothic, Renaissance, Baroque, as well as many oriental elements, led to the emergence of eclecticism.

Fancy patterns are created from bindings. In fences, balcony railings, stairs design, everything is dominated by capricious curvilinear outlines, stylization of plant motifs, especially herbs, flowers, with curved stems and bizarre petal shapes.

In the 20th century, decorative forged metal was replaced by welded structures, which is associated with the development of rolling and stamping industries, artistic forging began to be simplified.

The variety of directions and concepts in architecture and applied arts contradicted the goals of the totalitarian regime that was being formed at that time. By the beginning of the 1930s, the authorities had established tight control over art and architecture. The main components of the Soviet decorative arts 1920-30s - simplicity and functionalism. The totalitarian government perceived the formal search for artists and architects as too apolitical, too democratic, not amenable to ideological control. The violation of democratic principles in the life of society was reflected in the creative atmosphere. The foundation of the creative process was violated - the artist's freedom of expression. The years of Stalinism are one of the most tragic periods in the history of art in our country. The method of socialist realism, shackled by the rigid framework of directives, is the only direction of art in the 30-50s. Blacksmithing was recognized as "bourgeois" and ceased to exist for a long time. Only after the collapse of the USSR and the fall of the socialist. systems blacksmith art got the opportunity for uncensored, creative development.

Currently, the popularity of forged products is growing. Decorating a house, garden, apartment and office with forged interior items has become "fashionable" among wealthy people. Nothing can transform, emphasize the individuality of an apartment, house, garden as truly beautiful and stylish forged interior details. And this is indisputable, since it is artistic forging that is one of the last "living" crafts in our age of standard products produced in mass circulation.

rebirth artistic forging is of great importance for modern arts and crafts.

Artistic forging makes it possible to create products that are unique in their beauty and virtuoso sophistication, ideally complementing architectural ensembles. The fire of the blacksmith's forge gives the dwelling high reliability and a special feeling of warmth, fanning it with the spirit of the high art of the past. Strength and elegance, thoughtful harmony of lines, clarity of contour - this is not a complete list of the advantages of forged items.

Manual artistic forging in the 19th century was supplanted by stamping and casting, interest in it returned only in the 20th century, when blacksmithing equipment was created and many labor-intensive operations became mechanized, which made it possible to produce forged products faster and better.

When meeting a rural smithy, many are surprised: why is it so small, and the windows in it are not visible at all. It turns out that everything was planned that way, because when blacksmiths forged a tool - axes, chisels, chisels, etc., it was necessary to harden it, and for this it is necessary to accurately withstand the heating temperature. And how to determine it - after all, there were no pyrometers at that time? So the blacksmiths recognized the temperature by the colors of heat, and in order not to be mistaken and to determine it more accurately, there should have been twilight in the forge, in which the metal glowed with yellow-red tints.

Americans studying cost blacksmith products, found that one hammer blow is worth one dollar, and a blacksmith's blow is worth ten dollars. And the question immediately arises: why does a hammerman working with a heavy hammer get only one dollar per blow, and a blacksmith with his small handbrake ten dollars? The answer is this: the hammerer only strikes with a hammer, and the blacksmith knows where and how to strike. He thinks even during the forging period and determines the impact force of his handbrake and hammer hammer, depending on the image of the finished product. A good blacksmith not only forges, but performs sacred duties.

The first president of the SA, George Washington (1732-1799), liked to forge in his spare time, and the Italian dictator Benito Mussolini (1883-1945) liked not only to forge, but also to pose for cameras with a hammer in his hands.

The kings and rulers themselves did not disdain to pick up a blacksmith's hammer, for example, the French king Charles 9 (1550-1574) was a talented master in forging locks and keys, Louis 13 of Bourbon (1601-1643) devoted all his free time to artistic forging, and Louis 14 even set up a forge for himself in the Palace of Versailles.

Among the Russian tsars, Ivan the Terrible (1530-1584) and Peter 1 (1672-1725) were lovers of forging. who took part in the forging of anchors at the Voronezh shipyard.

It is known that in some countries of Africa and Asia, only those who knew blacksmithing well were elected rulers.

At the end of the 18th century Russian educator V. Pevshin in his “Commercial Dictionary” wrote: “If the price of things was determined by their usefulness, iron should be considered the most precious of all metals: there are no arts or crafts in which this was not necessary, and whole fill books with one description of such things "

Practically in all states of Europe and Asia there are folk tales. epics, epics and myths about blacksmith heroes: in Greece it is the blacksmith god Hephaestus, in Rome - Vulcan, among the Germans - Wieland, among the Finns - Ilmarinets, among the Russians - Svarog, among the Buryats - the hero Geser, among the Scandinavians - Mimir, Celts - god-smith Goibniu.

In the 17th century, iron production from peasant-handicraft became industrial, and in 1631 the first Ural plant on the Nice River began to operate.

A steam hammer with a mass of falling parts of 3 tons was built in 1842 by James Nesmith (1808 - 1890) and two of his hammers in 1848 began working at the Yekaterinburg Mechanical Factory and the Votkinsk Shipyard.

In the Soviet Union, the revival of blacksmithing art began after the creation in 1975 in the Saltykovka suburb of Moscow of the Museum of Forging Science and Technology on the basis of the house and site of Professor Anatoly Ivanovich Zimin, the founder of the domestic forging and pressing machine building. This exhibition was the first blacksmith exhibition in the Soviet Union, and about fifty blacksmiths from different cities and republics.

For the first time, man began to forge native and meteorite metals as early as the Stone Age, and that is why blacksmithing is considered the most ancient craft associated with metal processing.

blacksmith craft

The history of the emergence and development of blacksmithing

The origins of blacksmithing go back to ancient times. We find the first mention of blacksmiths in the myths of ancient Greece: from the time when the divine blacksmith Hephaestus forged nails for the crucifixion of Prometheus on a Caucasian rock. This is where the history of blacksmithing began.

The name of Cain, the first son of Adam and Eve, etymologically means "blacksmith". Among his descendants was Tubal Cain, who chose blacksmith craft. The Bible identifies him as an inventor different kind copper and iron tools used both for agriculture and for military operations. One of the first mentions of blacksmiths is in the story of the construction of the Jerusalem Temple under King Shlomo. Among those who built the walls of Jerusalem under Nehemiah were blacksmiths who made doors and gates with locks and bolts. In Jerusalem, before its capture by the Romans in 70 BC, some streets and quarters were inhabited exclusively by blacksmiths.

In Russia, iron was known to the early Slavs. The oldest method of metal processing is forging. At first, ancient people beat spongy iron with mallets in a cold state in order to "squeeze the juice out of it", i.e. remove impurities. Then they began to heat the metal and give it the desired shape.

Already in the 7th-9th centuries. the Slavs have special settlements of metallurgists. Forges in Slavic settlements were located away from residential buildings, near rivers: the blacksmith constantly needed fire in the forge to soften the metal and water to cool the finished products. Blacksmithing was considered by the Slavs to be a mysterious and even witchcraft occupation. No wonder the very word "blacksmith" is related to the word "intrigues". The blacksmith, like the plowman, was a beloved hero of Slavic folklore.

In the products of the ancient Slavs, the ornament is very calm, and the images do not inspire fear in a person. A resident of the endless wilds, the ancient Slav saw in fantastic creatures that inhabited, as he believed, forests, waters and swamps, not so much his enemies as patrons. They protected and protected him. He felt involved in their lives, and therefore in art, in forged products, he sought to emphasize this indissoluble bond. The artistic tastes and skills that formed then did not disappear with the rise of feudalism and the adoption of Christianity.

The process of feudalization led to the formation in the 9th century. Kievan Rus, a large state that quickly gained fame throughout the world of that time.

The name of the legendary founder of the city of Kiev - Kiy - is related to the word "forge"; the name itself could mean "club", "hammer". In Ukraine, legends are known about how a blacksmith harnessed a monstrous snake to a plow and forced it to plow furrows that became riverbeds or were preserved in the form of ancient fortifications - “serpent shafts”. In these legends, the blacksmith is not only the creator of handicraft tools, but also the creator of the surrounding world, the natural landscape.

The complexity of the process singled out blacksmiths from the community and made them the first artisans. In ancient times, blacksmiths themselves smelted the metal and then forged it. The necessary accessories of a blacksmith - a forge (smelting furnace) for heating a cracker, a poker, a crowbar (pick), an iron shovel, an anvil, a hammer (sledgehammer), a variety of tongs for extracting red-hot iron from the furnace and working with it - this is a set of tools necessary for melting and forging works.

For Kievan Rus, the adoption of Christianity was of progressive importance. It contributed to a more organic and deeper assimilation of all the best that Byzantium, which was advanced for that time, had.

In the X-XI centuries, thanks to the development of metallurgy and other crafts, the Slavs had a plow and a plow with an iron plowshare. On the territory of ancient Kiev, archaeologists find sickles, door locks and other things made by blacksmiths, gunsmiths and jewelers.

In the 10th century, above-ground stoves appeared, the air was pumped into them with the help of leather bellows. The furs were inflated by hand. And this work made the cooking process very difficult. Archaeologists still find signs of local metal production on the settlements - waste from the cheese-making process in the form of slag.

In the 11th century, metallurgical production was already widespread both in the city and in the countryside. The raw material for obtaining iron was swamp and lake ores, which did not require complex technology for processing and were widespread in the forest-steppe. The Russian principalities were located in the zone of ore deposits, and blacksmiths were almost everywhere provided with raw materials.

Very quickly, the culture of Kievan Rus reached a high level, competing with the culture not only of Western Europe, but also of Byzantium. Kiev, one of the largest and richest cities in Europe in the 11th-12th centuries, experienced a brilliant heyday. According to Titmar of Merseburg, a German writer of the early 11th century, there were several hundred churches and many markets in Kiev, which indicates a brisk trade and vigorous building activity. The applied art of Kievan Rus, the art of blacksmiths, was distinguished by high skill. Having gained distribution in everyday life, it equally manifested itself in cult objects (salaries, carved icons, folding crosses, church utensils, etc.).

Written sources have not preserved to us the forging technique and the basic techniques of ancient Russian blacksmiths. But the study of ancient forged products allows historians to say that the ancient Russian blacksmiths knew all the most important techniques: welding, punching holes, torsion, riveting plates, welding steel blades and hardening steel. In each forge, as a rule, two blacksmiths worked - a master and an assistant. In the XI-XIII centuries. the foundry partly became isolated, and the blacksmiths took up the direct forging of iron products. In Ancient Russia, any metal worker was called a blacksmith: "blacksmith of iron", "blacksmith of copper", "blacksmith of silver".

The simplest forged products include: knives, hoops and buds for tubs, nails, sickles, braids, chisels, awls, shovels and pans, i.e. items that do not require special techniques. Any blacksmith alone could make them. More complex forged products: chains, door breaks, iron rings from belts and harnesses, bits, lighters, spears - already required welding, which was carried out by experienced blacksmiths with the help of assistants.

The production of weapons and military armor was especially developed. Swords and battle axes, quivers with arrows, sabers and knives, chain mail, helmets and shields were produced by master gunsmiths. The manufacture of weapons and armor was associated with especially careful metal processing, requiring skillful work techniques. Russian helmets-shishaks were riveted from iron wedge-shaped strips. The well-known helmet of Yaroslav Vsevolodovich, thrown by him on the battlefield of Lipetsk in 1216, belongs to this type of helmet. It is an excellent example of Russian weapons and jewelry of the XII-XIII centuries.

In the XI-XIII centuries, urban craftsmen worked for a wide market, i.e. production is on the rise.

In the XIII century, a number of new craft centers were created with their own characteristics in technology and style. But we do not observe any decline in the craft from the second half of the 12th century, as it is sometimes asserted, either in Kiev or in other places. On the contrary, culture grows, covering new areas and inventing new techniques. In the second half of the 12th century and in the 13th century, despite the unfavorable conditions of feudal fragmentation, Russian craft reached its fullest technical and artistic flourishing. The development of feudal relations and feudal ownership of land in the XII - the first half of the XIII century. caused a change in the form of the political system, which found its expression in feudal fragmentation, i.e. creation of relatively independent states-principalities. During this period, blacksmithing, plumbing and weapons, forging and stamping continued to develop in all principalities. In rich farms, more and more plows with iron shares began to appear. Masters are looking for new ways of working. Novgorod gunsmiths in the 12th-13th centuries, using new technology, began to manufacture saber blades of much greater strength, hardness and flexibility.

In the architecture of Ukraine 14-17 centuries. Fortress architecture was of great importance. The territory of Ukraine then represented the arena of fierce struggle (Poland, Lithuania, Hungary), was subjected to devastating raids of the Tatar and then Turkish hordes. As a result, the products of blacksmiths also served to protect the fatherland, and decorative means were used very restrainedly.

From the middle of the XIII century, the dominion of the Golden Horde was established over Kievan Rus. Events 1237 - 1240 became perhaps the most tragic in the centuries-old history of our people. The cities of the Middle Ages suffered irreparable damage. The craftsmanship accumulated over the centuries was almost lost. After the Mongol conquest, a number of techniques familiar to Kievan Rus disappeared, and archaeologists did not find many objects common to the era preceding the yoke. Because of the Tatar-Mongol yoke in the XIII-XV centuries. there has been a significant lag in the development of the cities of feudal Russia from the cities of Western Europe, in which the bourgeois class begins to emerge. A small number of household items of the 14th-15th centuries have survived to our time, but even they make it possible to judge how the development of crafts in Russia gradually resumed. From the middle of the XIV century. a new boom in handicraft production began. At this time, especially in connection with the increased military needs, iron processing became more widespread, the centers of which were Novgorod, Moscow and other Russian cities.

In the second half of the XIV century. For the first time in the country, Russian blacksmiths made forged and riveted cannons. An example of the high technical and artistic skill of Russian gunsmiths is the steel spear of the Tver prince Boris Alexandrovich, which has survived to this day, made in the first half of the 15th century. It is decorated with gilded silver depicting various figures.

From the middle of the 16th century in Ukrainian architecture, the influence of Renaissance art is felt. The influence of northern Italian, German and Polish art is most noticeable in the architecture and applied arts of the cities of Western Ukraine, especially Lviv. The spirit of medieval aloofness and asceticism was replaced by secular aspirations. The motives of nature, inspired by the landscapes of the Carpathian region, are lovingly conveyed in the products of blacksmith masters. The ornament, decoration "vine" has found wide application.

In full force, the artistic features of iron were revealed later, especially in Ukrainian art of the 17th-18th centuries.

Window openings were closed with openwork wrought iron bars, gardens and parks were decorated with skillfully made wrought iron fences and wrought iron gates. Richly decorated iron doors with forging elements decorated stone temples, palaces, in the construction of which masters of all types of crafts took part.

In the 18th century, forging was widely used to make fences for city estates, mansions, and churchyards. The technique of iron casting competes with it, displacing forging as an expensive work. But the originality of artistic solutions, which is achieved by forging, retains interest in it in the 19th century.

In 1837 A new master plan for Kiev was approved. In 1830-50s. a number of large public and administrative buildings were built in the city: the Institute of Noble Maidens (1838-42 architect V.I. Beretti), the Kiev University Ensemble (1837-43 Beretti), offices (1854-57 M.S. Ikonnikov ). A new type of buildings appeared - tenement houses, which had floors for shops, a hotel, a restaurant, an office.

The fantasy and skill of blacksmiths, ingenuity, virtuoso mastery of technology, excellent knowledge of the features and capabilities of metal made it possible to create highly artistic works of blacksmithing, an infinitely large and expressive world of forged metal.

The use of forms of various historical styles - Gothic, Renaissance, Baroque, as well as many oriental elements, led to the emergence of eclecticism.

Fancy patterns are created from bindings. In fences, balcony railings, stairs design, everything is dominated by capricious curvilinear outlines, stylization of plant motifs, especially herbs, flowers, with curved stems and bizarre petal shapes.

In the 20th century, decorative forged metal was replaced by welded structures, which is associated with the development of rolling and stamping industries, artistic forging began to be simplified.

The variety of directions and concepts in architecture and applied arts contradicted the goals of the totalitarian regime that was being formed at that time. By the beginning of the 1930s, the authorities had established tight control over art and architecture. The main components of the Soviet decorative art of 1920-30s are simplicity and functionalism. The totalitarian government perceived the formal search for artists and architects as too apolitical, too democratic, not amenable to ideological control. The violation of democratic principles in the life of society was reflected in the creative atmosphere. The foundation of the creative process was violated - the artist's freedom of expression. The years of Stalinism are one of the most tragic periods in the history of art in our country. The method of socialist realism, shackled by the rigid framework of directives, is the only direction of art in the 30-50s. Blacksmithing was recognized as "bourgeois" and ceased to exist for a long time. Only after the collapse of the USSR and the fall of the socialist. blacksmithing system got the opportunity for uncensored, creative development.

Currently, the popularity of forged products is growing. Decorating a house, garden, apartment and office with forged interior items has become "fashionable" among wealthy people. Nothing can transform, emphasize the individuality of an apartment, house, garden as truly beautiful and stylish forged interior details. And this is indisputable, since it is artistic forging that is one of the last "living" crafts in our age of standard products produced in mass circulation.

The revival of artistic forging is of great importance for modern arts and crafts.

Blacksmithing today

The artistic processing of metal has undergone a significant evolution over its many years of existence, there have been times of prosperity and decline. But it's good that people still have a desire to revive traditions and create useful and beautiful things from metal.

Fortunately, interest in artistic processing metal, when various metal products are mass-produced due to the development of industry. The proof of this is the desire of people to completely different professions master the secrets of metal processing and make one or another product with your own hands.

In our time, the demand for art objects is increasing and quality standards are rising. art products, which are the decoration of people's lives.

Decorative and applied arts is a large area of art that serves to decorate the environment created by man.

Neither Soviet power nor modern globalization can destroy the living blacksmith spirit in Ukraine.

For a long time in the village, the blacksmith was the most noble person, they were associated with something mysterious, mysterious, unknown to other people, because not everyone knew the secrets of how to deal with metal and produce the necessary things.

Blacksmiths were approached by people with different needs: to make plowshares, to shoe a horse, to make weapons, nails or some kind of household equipment. If you study the culture and epic of our people more deeply, you can find many musical and poetic works, legends, fairy tales in which the blacksmith is honored. Now, as soon as we imagine what strength it was necessary to have in order to hold the sword that blacksmiths made for the warriors of the time of Kievan Rus, modern men may not be able to hold it in their hands.

Our Ukrainian village has preserved these traditions despite the policy of the Soviet government towards Ukraine. Although the blacksmiths then could only produce something from the rural inventory - no more. And the art of artistic forging disappeared completely. The revival began several decades ago, built only on the enthusiasm of some masters, such as Anatoly Ignashchenko and Oleg Stasyuk, they lived this art.

Connoisseurs of domestic artistic forging consider it a great success that in Western Ukraine the craftsmen have preserved purely Ukrainian elements of forging, which are not repeated anywhere in the world, and traditional forging is widespread in our country: due to the vocation of the soul or for material necessity, forging in Ukraine develops and people find themselves in this folk industry.

Bogdan Popov, well-known in the domestic blacksmith society, is from Kiev. Having made a real sword for himself for the first time in his life, he was forever carried away by working with metal. For 20 years, Bogdan has been interested in ancient Russian blacksmithing, which he considers a standard in art. He has a practice in the manufacture of ancient Russian swords, axes, etc.

Also, Bogdan organized a school, or something like a club, for those who are interested in blacksmithing, where you can learn this ancient craft. The main thing is not to have the strength, but the desire to do such work, - says Bogdan.

During the blacksmith's day, this school presented several types of field forges. Among them was a Japanese forge. It is very interesting, along with the traditional Ukrainian smithy, to show how it was in other nations, because earlier, in ancient times, each nation had its own forges. Next time Bogdan plans to show an Indonesian or African forge.

Bogdan's school is developing in the direction of traditional blacksmithing, but along with this, his colleague Dmitry Kushnir, who is fond of highly artistic forging, works. He produces exquisite things of amazing shape. These are fantastic animals and various decorations, original vases, etc. This is an elite trend in artistic forging (in terms of beauty and value). All his works are purely copyright, it is impossible to duplicate them.

In general, many talented blacksmiths work in Ukraine in different cities and regions. Therefore, every year several festivals and competitions are held on blacksmithing. This further popularizes this kind of ancient traditional art form and inspires young people to acquire and develop this profession, developing blacksmithing itself.

There were also festivals of arts from the blacksmith craft, held at the interstate level. Guests from other countries of the world came and there was an opportunity to exchange experiences and feel that we are all different, but we are one family, that we all strive for beauty, which manifests itself through the disclosure and development of our abilities and talents in different areas and areas.

FORGING- this is one of the methods of processing metals by pressure, in which the tool has a repeated intermittent effect on the workpiece, as a result of which, while deforming, it gradually acquires a given shape and size. Everyone knows that since ancient times, cold forging of copper, native iron has been, perhaps, the most basic method of metal processing.

Cold forging was used by the Indians of North and South America until the 16th century BC. Later, hot forging began to be used in Iran, Mesopotamia, and Egypt in the 4th-3rd centuries. BC.

The first craftsman in ancient Russia was a blacksmith. It is with him that many different legends and beliefs are associated. The patron of blacksmiths and artisans, the god of fire and blacksmithing in Ancient Greece- Hephaestus, the son of Zeus and Hera, unlike other Olympic gods, physical labor was at a premium. He was often depicted as a blacksmith working in his sooty workshop in the bowels of the fire-breathing Etna. It was he who forged the scepter of Zeus, the rod of Dionysus, the armor of Achilles and the weapons of Hercules. In Slavic-Russian mythology, Hephaestus is identified with the pagan blacksmith god Svarog, who in Christianity turned into saints Kuzma and Demyan (Kozmodemyan). It is not surprising that, under the auspices of the Russian Hephaestus - the god Svarog, a blacksmith can not only forge a plow or sword, but also heal illnesses, arrange weddings, tell fortunes, and drive away evil spirits from the village. In epic tales, it was the blacksmith who defeated the Serpent Gorynych, chaining him by the tongue.

In Russia, iron was known to the early Slavs. The oldest method of metal processing is forging. At first, ancient people beat spongy iron with mallets in a cold state in order to "squeeze the juice out of it", i.e. remove impurities. Then they guessed to heat the metal and give it the desired shape. V X – XI centuries Thanks to the development of metallurgy and other crafts, the Slavs had a plow and a plow with an iron plowshare. On the territory of ancient Kiev, archaeologists find sickles, door locks and other things made by blacksmiths, gunsmiths and jewelers.

V XI century metallurgical production was already widespread, both in the city and in the countryside. The raw material for obtaining iron was swamp and lake ores, which did not require complex technology for processing and were widespread in the forest-steppe. The Russian principalities were located in the zone of ore deposits, and blacksmiths were almost everywhere provided with raw materials. Finding iron ore was no more difficult than finding pottery clay. Swamp ore retained its importance for the metallurgical industry of some regions of the country until the 18th century. Small factories worked on it with a semi-mechanized blowing process - a mill drive. By appearance swamp ore is dense, heavy, earthy clods of a reddish-brown hue. It sometimes lies in the ground in layers up to 30 cm thick, but more often at the bottom of swamps and lakes. She was scouted with a pole and scooped up with long-handled ladles. Usually iron ore was mined in August. Then it was dried and burned on fires in the middle of autumn.

The most difficult and responsible business was the smelting of iron from ore. It was carried out in winter with the help of the so-called cheese-blowing process- injection of cold air into the furnace, necessary for the reduction of iron. Iron oxides in the form of iron ore, poured into the furnace on top of burning coal, as a result chemical reactions they lost oxygen and at a temperature of 700-800 degrees C turned into iron, which in the form of a thick pasty mass (spongy spongy cracker) flowed into the lower part of the furnace. The temperature of 1500-1600 degrees C, necessary for the transformation of iron into a liquid state, was inaccessible to the ancient metallurgists, therefore the process of smelting iron at that time was called "boiling". The disadvantage of this method was low interest smelting metal from ore. Part of the metal remained in the ore. In the area of ore occurrence, almost every village had its own smelters (houses), in the raw furnaces of which iron was smelted - the most difficult of the works.

The first raw-hearth was an ordinary hearth in a dwelling. Special bugles appeared later. For fire safety purposes, they were located at the edge of the settlements. The early kilns were round pits one meter in diameter thickly covered with clay, dug into the ground. Their popular name is "wolf pits". V X century ground furnaces appeared, the air was pumped into them with the help of leather bellows. The furs were inflated by hand. And this work made the cooking process very difficult. Archaeologists still find signs of local metal production on the settlements - waste from the cheese-making process in the form of slag. At the end of the “cooking” of iron, the domnitsa was broken, foreign impurities were removed, and the kritsa was removed from the furnace with a crowbar. The hot cry was captured by pincers and carefully forged. Forging removed slag particles from the surface of the crown and eliminated the porosity of the metal. After forging, the kritsa was again heated and again placed under the hammer. This operation was repeated several times. For a new smelting, the upper part of the house was restored or rebuilt. In later domnitsa, the front part was no longer broken, but disassembled, and the molten metal flowed into clay containers.

But, despite the wide distribution of raw materials, iron smelting was carried out by far not in every settlement. The complexity of the process singled out blacksmiths from the community and made them the first artisans. In ancient times, blacksmiths themselves smelted the metal and then forged it. Necessary accessories for a blacksmith - a forge (smelting furnace) for heating a cracker, a poker, a crowbar (pick), an iron shovel, an anvil, a hammer (sledgehammer), a variety of tongs for extracting red-hot iron from the furnace and working with it - a set of tools necessary for smelting and forging works.

The hand forging technique remained almost unchanged until the 19th century, but even fewer authentic ancient forges of history are known than domnits, although archaeologists periodically discover many forged iron products in settlements and mounds, and their tools in the burials of blacksmiths: pincers, hammer, anvil, casting accessories . Written sources have not preserved to us the forging technique and the basic techniques of ancient Russian blacksmiths. But the study of ancient forged products allows historians to say that Old Russian blacksmiths knew all the most important techniques: welding, punching holes, torsion, riveting plates, welding steel blades and hardening steel. In each forge, as a rule, two blacksmiths worked - a master and an assistant. V XI-XIII centuries the foundry partly became isolated, and the blacksmiths took up the direct forging of iron products. In Ancient Russia, any metal worker was called a blacksmith: "blacksmith of iron", "blacksmith of copper", "blacksmith of silver".

Simple forged products were made with a chisel. The technology of using an insert and welding a steel blade was also used. The simplest forged products include: knives, hoops and buds for tubs, nails, sickles, braids, chisels, awls, shovels and pans, i.e. items that do not require special techniques. Any blacksmith alone could make them. More complex forged products: chains, door breaks, iron rings from belts and harnesses, bits, lighters, spears - already required welding, which was carried out by experienced blacksmiths with the help of assistants.

Masters welded iron, heating it to a temperature of 1500 degrees C, the achievement of which was determined by sparks of white-hot metal. Holes were punched with a chisel in ears for tubs, plowshares for plows, hoes. The puncher made holes in scissors, tongs, keys, boat rivets, on spears (for fastening to the pole), on the shrouds of shovels. The blacksmith could carry out these techniques only with the help of an assistant. After all, he needed to hold a red-hot piece of iron with tongs, which, when small sizes it was not easy for the anvils of that time, to hold and guide the chisel, to hit the chisel with a hammer.

It was difficult to make axes, spears, hammers and locks. The ax was forged using iron inserts and welding strips of metal. Spears were forged from a large triangular piece of iron. The base of the triangle was twisted into a tube, a conical iron insert was inserted into it, and then the spear bushing was welded and a rampage was forged. Iron cauldrons were made from several large plates, the edges of which were riveted with iron rivets. The iron twisting operation was used to create screws from tetrahedral rods.

The above range of blacksmith products exhausts all the peasant inventory needed to build a house, Agriculture, hunting and defense. Old Russian blacksmiths X-XIII centuries mastered all the basic techniques of iron processing and determined the technical level of the village forges for centuries. The basic form of sickle and short-handled scythe were found in the 9th-11th centuries. Old Russian axes have undergone a significant change in the X-XIII centuries. acquired a form close to modern. The saw was not used in rural architecture. Iron nails were widely used for carpentry work. They are almost always found in every burial with a coffin. The nails had a tetrahedral shape with a bent top.

By the 9th-10th centuries, patrimonial, rural and urban crafts already existed in Kievan Rus. Russian urban craft entered the 11th century with a rich stock of technical skills. Village and city were still completely separated until that time. Served by artisans, the village lived in a small closed world. The sales area was extremely small: 10-15 kilometers in radius. The city blacksmiths were more skilled craftsmen than the village blacksmiths. During the excavations of ancient Russian cities, it turned out that almost every city house was the dwelling of an artisan. From the beginning of the existence of the Kievan state, they showed great skill in forging iron and steel of a wide variety of objects - from a heavy plowshare and a helmet with patterned iron lace to thin needles; arrows and chain mail rings riveted with miniature rivets; weapons and household implements from barrows of the 9th-10th centuries. In addition to blacksmithing, they owned metalwork and weapons. All these crafts have some similarities in the ways of working iron and steel. Therefore, quite often artisans engaged in one of these crafts combined it with others. In the cities, the technique of smelting iron was more perfect than in the countryside. City forges, as well as domnitsa, were usually located on the outskirts of the city.

The equipment of urban forges differed from the village ones - by greater complexity. The city anvil made it possible, firstly, to forge things that had a void inside, for example, a tribe, spear bushings, rings, and most importantly, it allowed the use of an assortment of figured linings for forgings of a complex profile. Such linings are widely used in modern blacksmithing when forging curved surfaces. Some forged products, starting from the 9th-10th centuries, bear traces of processing with the help of such linings. In those cases where two-sided processing was required, both the lining and the chisel-stamp of the same profile were obviously used to make the forging symmetrical. Linings and stamps were also used in the manufacture of battle axes. The assortment of hammers, blacksmith tongs and chisels of urban blacksmiths was more diverse than that of their village counterparts: from small to huge.

Beginning with IX-X centuries Russian craftsmen used files to process iron. Old Russian city forges, metalwork and weapons workshops in the X-XIII centuries. had: forges, furs, simple anvils, anvils with a spur and a notch, inserts into the anvil (of various profiles), sledgehammer hammers, handbrake hammers, billhook hammers (for cutting) or chisels, punch hammers (beards), hand chisels, manual punches, simple tongs, tongs with hooks, small tongs, vise (primitive type), files, circular sharpeners. With the help of this diverse tool, which does not differ from the equipment of modern forges, Russian craftsmen prepared many different things. Among them are agricultural implements (massive plowshares and coulters, plow knives, scythes, sickles, axes, honey cutters); tools for craftsmen (knives, adzes, chisels, saws, scrapers, spoons, punches and figured hammers of chasers, knives for planes, calipers for ornamenting bones, scissors, etc.); household items (nails, knives, ironed arks, door breaks, staples, rings, buckles, needles, steelyards, weights, cauldrons, hearth chains, locks and keys, ship rivets, armchairs, bows and hoops of buckets, etc.); weapons, armor and harness (swords, shields, arrows, sabers, spears, battle axes, helmets, chain mail, bits, spurs, stirrups, whips, horseshoes, crossbows).

V IX-XI centuries locks are already in use in Russian cities various systems and various forms. Basically they were delivered from the countries of the East. V XI-XII century in the Middle Dnieper region, mass production of tubular copper locks of a standard form is being established. The design of the lock is improved by adding devices that eliminate the possibility of unlocking it without a key. In the near abroad, castles were widely known, colloquially called "Russian". The original complete isolation of artisans is beginning to be broken.

The production of weapons and military armor was especially developed. Swords and battle axes, quivers with arrows, sabers and knives, chain mail and shields were produced by master gunsmiths. The manufacture of weapons and armor was associated with especially careful metal processing, requiring skillful work techniques. Although the swords that existed in Russia in the 9th-10th centuries are mostly Frankish blades, archaeologists, nevertheless, in their excavations discover the presence of artisans-gunsmiths among Russian townspeople of the 9th-10th centuries. In a number of burials, bundles of forged rings for iron chain mail were found, which are often found in Russian military barrows from the 9th century. The ancient name of chain mail - armor - is often found on the pages of the annals.

Making chain mail was labor intensive. Technological operations included: iron wire forging, welding, joining and riveting of iron rings. Archaeologists discovered the burial of a chain mail master of the 10th century. In the 9th-10th centuries, chain mail became an obligatory accessory of Russian armor. The ancient name of chain mail - armor - is often found on the pages of the annals. True, opinions are expressed about the origin of Russian chain mail about receiving them either from nomads or from the countries of the East. Nevertheless, the Arabs, noting the presence of chain mail among the Slavs, do not mention their import from outside. And the abundance of chain mail in the guard mounds may indicate that chain mail craftsmen worked in Russian cities.

The same applies to helmets. Russian historians believe that the Varangian helmets differed too sharply in their conical shape. Russian helmets-shishaks were riveted from iron wedge-shaped strips. The well-known helmet of Yaroslav Vsevolodovich, thrown by him on the battlefield of Lipetsk in 1216, belongs to this type of helmet. It is an excellent example of Russian weapons and jewelry of the XII-XIII centuries. The tradition has affected the overall shape of the helmet, but technically it is very different from the helmets of the 9th-10th centuries. Its entire body is forged from one piece, and not riveted from separate plates. This made the helmet significantly lighter and stronger. Even more skill was required from the master gunsmith.

An example of jewelry work in the weapons technology of the XII-XIII centuries is a light steel hatchet, believed to be made by Prince Andrei Bogolyubsky. The surface of the metal is covered with notches, and on these notches (in the hot state) sheet silver is stuffed, on top of which an ornament is applied with engraving, gilding and niello.

Oval or almond-shaped shields were made of wood with an iron core and iron fittings.

A special place in blacksmithing and weapons business was occupied by steel and hardening of steel products. Even among the village kurgan axes of the 11th-13th centuries, a welded-on steel blade is found. Steel's hardness, flexibility, easy weldability and ability to accept hardening were well known to the Romans. But hardfacing steel has always been considered the most difficult task in all blacksmithing, because. iron and steel have different welding temperatures. Steel hardening, i.e. more or less rapid cooling of a red-hot object in water or in another way is also well known to the ancient blacksmiths of Russia. Urban blacksmithing was distinguished by a variety of techniques, the complexity of the equipment and the many specialties associated with this production.

V XI-XIII centuries urban craftsmen work for a wide market, i.e. production is on the rise. The list of urban artisans includes ironsmiths, domniks, gunsmiths, armor makers, shield makers, helmet makers, arrow makers, locksmiths, nail makers.

V XII century craft development continues. In metal, Russian masters embodied a bizarre mixture of Christian and archaic pagan images, combining all this with local Russian motifs and plots. Improvements continue in the craft technique aimed at increasing the mass production. Posad craftsmen imitate the products of court craftsmen. In the XIII century, a number of new craft centers were created with their own characteristics in technology and style. But we do not observe any decline in the craft from the second half of the 12th century, as it is sometimes asserted, either in Kiev or in other places. On the contrary, culture grows, covering new areas and inventing new techniques.

In second half of the 12th century and in the 13th century Despite the unfavorable conditions of feudal fragmentation, Russian craft reached its fullest technical and artistic flourishing. The development of feudal relations and feudal ownership of land in the XII - the first half of the XIII century. caused a change in the form of the political system, which found its expression in feudal fragmentation, i.e. creation of relatively independent states-principalities. During this period, blacksmithing, plumbing and weapons, forging and stamping continued to develop in all principalities. In rich farms, more and more plows with iron shares began to appear. Masters are looking for new ways of working. In the 12th-13th centuries, Novgorod gunsmiths, using a new technology, began to manufacture saber blades of much greater strength, hardness and flexibility.

WITH mid-13th century over Russia, the dominion of the Golden Horde was established. Events 1237 - 1240 became perhaps the most tragic in the centuries-old history of the Russian people. The Russian cities of the Middle Ages suffered irreparable damage. The craftsmanship accumulated over the centuries was almost lost. After the Mongol conquest, a number of techniques familiar to Kievan Rus disappeared, and archaeologists did not find many objects common to the era preceding the yoke.

Because of the Tatar-Mongol yoke in the XIII-XV centuries. there has been a significant lag in the development of the cities of feudal Russia from the cities of Western Europe, in which the bourgeois class begins to emerge. A small number of household items of the 14th-15th centuries have survived to our time, but even they make it possible to judge how the development of crafts in Russia gradually resumed.

WITH mid-14th century a new boom in handicraft production began. At this time, especially in connection with the increased military needs, iron processing became more widespread, the centers of which were Novgorod, Moscow and other Russian cities. In second half of the 14th century. For the first time in the country, Russian blacksmiths made forged and riveted cannons. An example of the high technical and artistic skill of Russian gunsmiths is the steel spear of the Tver prince Boris Alexandrovich, which has survived to this day, made in the first half of the 15th century. It is decorated with gilded silver depicting various figures. There is evidence that the works of Russian gunsmiths (shells and other armor) were exported to the Crimean Khanate. Golden Horde, overthrown in 1480, for another two centuries made itself known to the Russian state with its raids with the support of Turkey, as well as the Kazan, Astrakhan, Crimean and Siberian Khanates.

And yet, in end of the 15th - first half of the 16th century. a unified Russian state was formed. Moscow became the main center of handicraft production and trade throughout the Russian state. At the end of the 15th century, the grand dukes began to arrange large-scale events in Moscow for that time manufacturing enterprises. One of the first was a cannon hut, later transformed into a cannon yard - the arsenal of the Russian army. A whole school of masters developed here, to which the famous Andrey Chokhov, cast 2400 pood "Tsar Cannon".

V first quarter of the 16th century The Russian state, having united the Russian lands, was a large, but relatively compact territory with a historical center in the interfluve of the Oka and Volga, mainly inhabited by Great Russians.

Since end of the 15th to the middle of the 17th centuries. in the Russian state a system of serfdom took shape, which placed millions of peasants in a position of personal dependence on the feudal lords. The technical development of the country has slowed down. But, nevertheless, certain shifts in handicraft production still took place. In the 16th century, more complex blast furnaces for smelting iron from ore appeared, replacing the raw furnaces. The volume of metal processing has increased. A lot of new craft specialties related to metal processing appeared. Worked alongside the blacksmiths nailers, cutlers, sabelniks, archers, armourers, chain mailers, brackets, ploughshares, horseshoes, axes, frying pans, hammers, hammers, squares, locks, self-piercing guns, trunks. In the 16th century, technical advances made it possible to use already mechanical hammers - "samokovy", set in motion by water (water drive). The weight of the falling striker increased to 400 kg (i.e., 10-15 times), and the force of its impact increased significantly.

However, the heyday of forging came at the end of the Middle Ages and the beginning of the New Age, that is, in the 16th-18th centuries. In particular, in the troops of Ivan the Terrible, forged cannons, which Russian craftsmen produced by hand, terrified the enemies.

But forging technologies were rapidly improving, and already in XVIII century, in the fateful era of Peter I, arms factories started operating in Russia. In them, guns were no longer made by hand, but with the help of forging lever hammers on a water drive.

stamping was first used at the most famous arms factory in our country - Tula. It happened in 1800, and the pioneer of this method was the blacksmith Pastukhov. And in the middle of the 19th century, technology stepped forward even further: steam hammers, and then they gave way to presses (hydraulic machines).

The profession and work of a blacksmith were honorable and valued from ancient times. The most common Russian surname is still not "Ivanov", as many people think, but "Kuznetsov" (as in England, the analogue of this surname is Smith). This suggests that the blacksmith has always occupied a significant place in any society.

In Russia, forging traditions are closely intertwined with national aesthetics and mentality, and with our national history. In different periods of the life of the state, their styles in architecture and sculpture prevailed, and different aspects of the work of blacksmiths and casters were in demand. The art of forging developed in accordance with new advances in processing techniques and methods, since every new concept in forging required another step in technology. Therefore, the periodization of the development of artistic forging is associated with various sections of technology.

Technology for the production of metal products

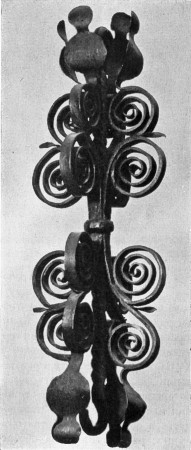

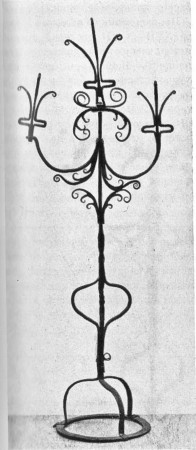

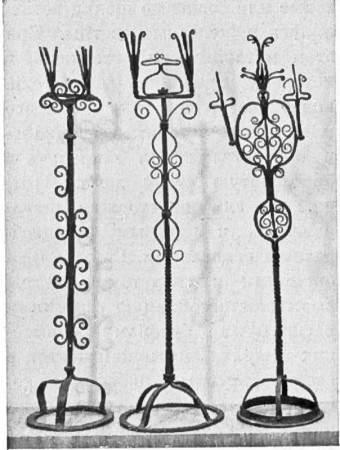

The most ancient forging was carried out by the same methods as the modern one. In ancient times, the blacksmith primarily forged household items. The most interesting elements of ancient life are forged svetets, that is, metal rods for a torch. A long splinter was inserted into the split at the upper end of the lantern, and a heavy hoop was attached to the lower end of the product in order to place the lantern horizontally. They did not put it anywhere, but in a bucket of water, so that the torch would not accidentally start a fire. Svetets is a fairly simple product that does not require time to manufacture. Therefore, the master could freely experiment with his composition, as well as work out new methods. Therefore, it was the experience of manufacturing simple household items that gave a lot of progress in forging technology in our country, including forging for architecture.

Blacksmiths showed creativity and imagination, decorating their creations with swirls and patterns. Svettsy became more beautiful and more diverse. The time came when, instead of the rod, they began to use an iron strip, the edges of which were cut and twisted into thin currencies. The upper end of the strip was also cut. There were many options for compositions, and each turned out to be unique.

These well-established techniques were subsequently inherited by blacksmiths who produced architectural products- decorative forged lattices in small niches, as well as in large openings and spaces, were decorated with such elements.

V XVII century there was a certain qualitative leap in artistic forging. In those days there was a restructuring of Moscow - from wood to stone.

Elements of artistic forging were used not only by church architecture, but also by secular ones. Basically, these techniques were used in the manufacture of gratings, moreover, according to a single, repeatedly repeating module. To fasten individual elements, either forge welding or forge riveting was used.

V XVIII century, the technology of forging gratings has undergone significant changes. At this stage, all blacksmith methods of metal processing were widely used, the elements are distinguished by the severity of the silhouette, but become more complicated due to the depth of space. There are also new elements: stars, flowers, sun, masks. Details are often cut from tin. In the 17th century, as already mentioned, the forged lattice was based on a repeating module, in accordance with the current style of Russian stone architecture, then the main style of the 18th century was Russian baroque- dictated new approaches. The scale of decor in the Russian Baroque is more round, it is characterized by large branches or garlands, which are superimposed on the general architectural rhythm. It is enough to look at the stucco molding of buildings of this style. Also in forging, the tendencies towards a complicated relief solution were reflected. Not the last role in this was played by the fact that many arms factories appeared in Russia and foundry production developed. It was closely associated with relief art. The rapid development of casting contributed to the successful development of cast-iron sculpture and the manufacture of architectural decorative details. At this time, they begin to make unique cast iron gratings, models for which are created by the greatest architects of Russia. Example - Cast-iron gates in Tolmachevsky Lane in Moscow. Forged elements were also combined with cast ones. This combination can be seen on some fences of the late eighteenth century.

A new step was taken by artistic forging in 19th century. It was a real age of harmony. Classicism at this time, it had long since replaced the baroque and spread everywhere, and under its influence, impressive spatial metal compositions were made on the balconies and fences of mansions. There were much fewer cast parts in the 19th century, forged ones prevailed, and cast ones seemed to be precious inserts among the forged settings. Graceful, unique compositions were created by high-class Russian architects: Gilardi, Beauvais, Bazhenov and Kazakov.

During the time of Peter the Great, all construction efforts were concentrated, as you know, in the city on the Neva, but starting from Catherine the Great, all Russian monarchs followed a different, unified urban planning policy that contributed to the development and prosperity of Russia. Built and transformed big cities European part Russian Empire: Moscow, Nizhny Novgorod, Kostroma and Kazan, entire streets were built up and separate new buildings were erected in many provincial centers. The difference between the monarchs consisted only in the fact that it was they who were inclined to build: some - courts and barracks, some - churches and majestic cathedrals, and some - palaces. But as a result, masterpieces of architecture of the 19th century stand all over the face of the country, decorating Russian cities.

In those days, Russian blacksmiths produced not only lattices and gates, but also highly artistic forged railings and lanterns.

But the golden age of classicism for Russian forging was replaced by another: the time has come Art Nouveau architecture. Outstanding representatives of this direction - Gipius, Goletsky, Shchusev, Shekhtel. During this period, when the silhouettes of buildings acquired a unique look, it took one more step forward. Forging in architecture is gaining new positions: they also began to forge roof ridges and porch visors.

The Soviet period is coming - from 1930 to 1950. At this time, forging is almost not used - it was replaced by artistic casting. At that time, state and public official buildings were decorated with architectural and spatial metal compositions.

Yes and after 1960 casting and hot stamping occupied leading positions, displacing forging almost completely. It seems that the craft and art of a blacksmith at that time began to slowly die, being completely unclaimed.

But in 70s of the last century, sculptors suddenly flared up with an interest in forged metal. It turned out that sheet metal products are cheaper than cast ones. At that time, they began to make a metal base for sculptural compositions from profiled metal. A striking example is the famous clock of the Central Puppet Theatre. The sculptor Shakhovsky created this composition in 1971. It clearly shows the use of forging motifs revived from the past. The term "graphic sculpture" appeared, and entire compositions were created in this category. In the same period, gratings began to be made in a new way, following a strict geometric style. And so in the mid 80s one could already hear about the hot working of metals.

V our days there is a new flourishing of artistic forging. Restoration is underway, old traditions and styles are being revived, and old houses in urban centers are acquiring a solemn and harmonious look thanks to the creation of lattices on windows and wrought iron gates.

The history of blacksmithing and blacksmithing

Works of wrought iron of the XVII-XVIII centuries have historical and artistic value. In them, the originality of artistic images received a masterful embodiment in the material. The use of various methods of ornamentation, the richness and variety of patterns, the sense of the shape of an object make it possible to attribute them to the best achievements Russian artistic metal.

Russian blacksmithing has a long tradition. It developed in ancient times. For centuries, experience has been accumulated, blacksmithing techniques have been improved. Simple, but requiring certain significant skills, various objects were made from wrought iron: they bent thick rods for svets and gate rings, keys and cuts, forged and pulled iron ribbons for chests and caskets.

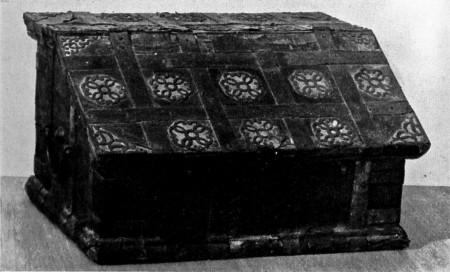

Caskets - "teremki". 17th century Great Ustyug.

It is difficult to trace the development of blacksmithing as one of the types of folk art in its entirety and consistency - a limited number of monuments have come down to us. It is also quite difficult to determine the time and place of their production, since items similar in nature and methods of ornamentation are found in different regions.

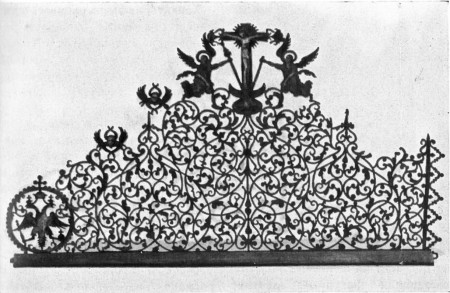

The top of the banner. 18th century

For many centuries in Russia there were crafts for processing iron. The history of their origin and development is connected with the sources of raw materials, with the growth of ore mining and iron smelting.

Demand for blacksmith products artistic craft was large, their sale was provided by wide trade. They were transported throughout Russia. In the XVI- XIX centuries significant forging productions were concentrated in Moscow, Ustyuzhna Zheloznopolskaya, Veliky Ustyug, Tula, Yaroslavl, Nizhny Novgorod. Each of these centers developed its own traditions, had its own talented and skilled craftsmen.

Headrest. 17th century

Blacksmith's craft played a significant role in the life of towns and villages. Craftsmen could shoe a horse and make a plow, forge a fence and make a new castle. But the names of those who skillful hands made amazingly beautiful products.

From time immemorial, the craft of a blacksmith was revered in Russia. His attitude was special. This occupation has always aroused a hidden interest among the people, the work of the master was surrounded by a certain haze of mystery and mystery. Not in vain, probably, in Russian fairy tales and songs, the blacksmith was the most cunning and smartest.

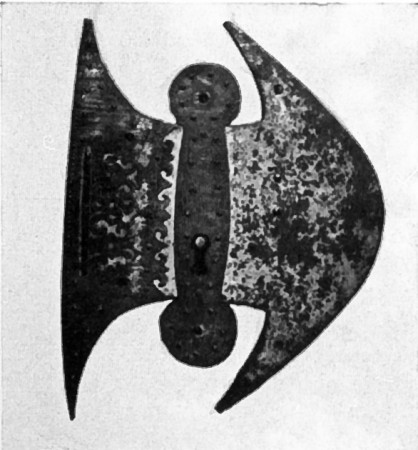

Ax lock. 18th century

This is probably why the ability to smelt ore, correctly guess the additions to iron, and the heating temperature was recognized as almost miraculous. And, perhaps, by right, Kuznetsov can be considered the first metallurgists and chemists. In Russia, the production of flash iron was established early, so called from the word "crown" - a piece of metal obtained by processing ore. After the slag was mechanically removed from it, the red-hot ingot was subjected to forging.

The premises for the forges were always strong and reliable. They were usually located outside the village or city. After all, blacksmithing is associated with fire, so often forges were built closer to a lake or river, in case of a fire. Sometimes they were just earthy. But built from dry, large logs, they served for eighty to a hundred years. But in vain the people said: "You will survive two huts, but it is difficult to survive the forge."

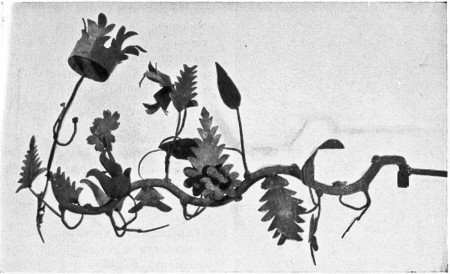

Bracket. 18th century

A necessary accessory for any forge was a forge - a brick oven with a hole for an air pipe - bellows. The workshop equipment is simple: anvils, hammers of various sizes and weights, files and chisels, pincers and tongs for holding red-hot blanks and horseshoes. The master rarely worked alone. Only when forging small items could he get by with a white assistant. The assistant usually put coals on, lit and fanned the fire, and set the bellows in motion. The blacksmith threw a piece of iron into the fire and glowed it white. If a piece of iron was small, then with one hand the blacksmith took it out with tongs and put it on the anvil, and with the other hand he forged an object of the desired shape with hammer blows. This operation required considerable physical effort and skill. If a large piece was forged, then the assistant left the bellows, took the hammer and worked together with the blacksmith. Several times the iron passed from the fire to the anvil, and then returned to the fire again for further incandescence. At the end of forging, the master lowered the product into the water. Then followed the assembly and finishing of the product. This is hard and painstaking work. Since ancient times, craftsmen have known such techniques as welding, turning, cutting, polishing, and soldering. Knowledge of these processing techniques made it possible to produce various tools, weapons, household items.