A dull knife is of little use - anyone who has tried to use it knows this. But not everyone understands why the knife becomes dull, and very few understand how to restore the razor sharpness of the knife. Sergey Mitin, the author of the book “How to Sharpen Knives Properly” and numerous publications on this topic, shares with us his vision of this multifaceted issue.

It has two sets of ceramic rods set at 20 degrees. Medium gray rods are sharpened, and thin white rods are honed. Norcark's 20 degree rates are ideal for fingerknife touches where the starting edge was 17 or 18 degrees. Ceramic is so hard and fine-grained that it looks more like steel. This setting allows you to slightly change the angle of the bevel.

Applying the knife at an angle reduces the bevel angle and gives more razor edge. It is so compact when telescopically closed that it can be carried in your jeans' watch pocket. The block is well padded and strong, and has a conical tooth for serrated blades.

Everyone knows that with use, each knife gradually dulls. Of course, it means correct use knife - for cutting what can and should be cut with a knife. A high-quality knife from a world-famous manufacturer will dull far less quickly than a “good and cheap” one from an unknown Far Eastern company. But even the best knife with a blade made of the most high-tech steel will sooner or later lose a fair amount of its cutting ability and require much more effort to work with it. So, it should be sharpened again.

Less expensive model available without conical tone. Electric knife sharpeners, such as those found on can openers, grind aggressively but with little control of angle or depth. Here are two sharpeners worth considering for home use. The instructions don't say much, but the designer recommends pulling the knife over the wheels a few times to even out the edge, using it as a hand sharpener. But this edge, straight from the machine, will cut right through a ripe tomato until a fine line can't.

Another reason for aggressive cutting would be an 18 degree canopy edge. Note: There is no generally accepted method for measuring the bevel angle of hollow blades. I like to measure wheel diameters and distance and calculate the angle at the edge with trigonometrics. The manufacturer suggests measuring the average angle of the entire bevel, which depends on the thickness of the blade. My low number is the angle at the edge, and my high number is the average angle for a blade with a thickness of 020 at the back of the bevel, typical of a hunting knife.

Why does a knife cut well, and when does it stop doing so? What happens to a blade when it gets dull? How to restore his sharpness, what needs to be done for this? In what way and with what tool? And most importantly - why should you do it this way, and not otherwise?

The sharpness of a blade is the ability to cut, and sharpening is precisely the process of making a blade sharp. Although sometimes these concepts are used interchangeably (for example, you can often hear the expression "the blade keeps sharpening well"). Without going into a very deep theory at the microscopic level, we can say that the cutting edge of the blade cuts the material, separating its particles from each other, and the wedge following it (and this is nothing more than a sharpening zone) in turn pushes the material apart, opening the cutting edge the possibility of moving to the lower, deep layers. With further deepening, the function of the wedge is taken over by the descent of the blade (no wonder it is called that!).

The wheels are diamond impregnated ceramic, consisting of 220 grams. From now on, you only use the second and third stages. Final honing at a very hard 25 degrees will give a very long life. Model 310 is similar but only with the last two steps. Don't forget to take care of your knife!

Microscope cutting

Removing the knife from the belt and stone

Hair sample. A sharp razor blade should cut the hanging hair held between two fingers smoothly about 1 cm from the fingers, no tricks. Marutti from a knife shop in Vienna recommend the following method: Hold the blade firmly against your hand, but do not lie, but 3-5 mm above the skin. The sharp edge will cut the hair, it will not be boring. If this hairstyle is successful, but not shaving or micrococcus, the blade may be uneven, pointed or hardened. Usually helps, but then peels off the skin again.The physical rule of the wedge operates on the cutting edge itself - the concentration of the applied force on a very narrow surface, measured literally in fractions of a micron (for comparison, the thickness of a human hair is about 50 microns). Nothing but a huge concentration of force per unit surface area (in other words, great pressure) allows the cutting edge to easily separate the particles of the material being cut, making it cutting. But at the same time, the cutting edge itself experiences exactly the same load from the material being cut. The force of action equals the force of reaction - hello from old Isaac Newton!

In any case, the new knife must be removed. After a few weeks of use, it will cut better, then "cut out". Then lightly rub your thumb along the cutting edge and hear a high, thin, chirping sound, like a distant cricket. In addition, when the blade is placed perpendicular to the thumb, the blade should rest on it with only its own weight, "stick lightly" and easily penetrate the skin. This is true for both shaving and a microtome knife, but when we make this pattern with a microtome knife, extra care is required because the knife is heavy and a tiny mishandling of the hand can cause disaster.

Why does the knife get dull

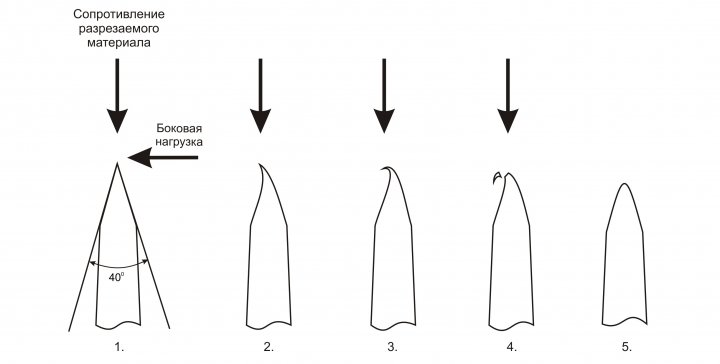

Why and how does the blade lose its sharpness? As a result of contact with the material being cut and its counteraction, particles of steel are torn off from the cutting edge of the blade, thereby changing its shape. And this process is quite active, precisely due to the huge concentration of effort on a very limited surface - it is always much easier to tear off something protruding.

In bloodthirsty detective films, we can see what a small, light razor can do. But the microtome knife is much more dangerous due to its wider and much longer blade and its enormous weight. To correct a little "small" in the ridge, the edge of the thumb nail is carefully and lightly pressed against the cutting edge of a razor or microtomy knife. With this, you can feel any slight unevenness of the cutting edge as a sharp obstacle. But this is not a test of sharpness, but the presence of ridges.

The fact that no one notices the first blow has not yet been proven. Often they come out of the ridge for the first time, and the irregularity is not felt until the second time. Pressure test. If the nail of the thumb is firmly pressed against the knife face from below under very slight pressure, the latter must be strongly bent. This shows if the facet of the knife is still thin enough to be improved by peeling the leather or stone to maximum sharpness. If it is not, then the knife must be inserted.

Damage occurs at two levels - micro- and macroscopic. Microparticles break off as a result of friction. The softer the steel of the blade and the harder the material being cut, the faster this happens. The nameless, inferior mild steel knife we use to carve hard, seasoned wood will dull a lot faster than the proprietary expertly tempered cutting edge supersteel knife we use to cut nothing but tomatoes. I mentioned, of course, completely extreme cases. But if the process of changing the shape of the cutting edge and the associated loss of sharpness were only limited to this - oh, how rarely we would have to sharpen our knives, even the most low-quality ones! Given the hardness and abrasiveness (ability to wear, cause wear) of tomatoes, there is practically no difference between the wear resistance of the best and worst knife steels. Even with hard wood, there would not be too much trouble if the wear of the cutting edge was limited only to the mechanism described above.

Producer's Razor, Jung's MicroMommersphere, Heidelberg. If the cutting edge is held on a bright light source, no sharp reflections are seen on the sharp edge, which is seen vertically from above, because it has little to no surface to reflect.

The quality of a cutting edge can also be determined fairly well with a stereo microscope, looking at it from the side and diagonally forward. View sample. A visual test is also performed during removal on the belt and stone. Normal bright field or optional with incident light, 30x to 200x magnification. Reflected light is also checked: the cutting edge should not have a surface, a dull one can be seen as a relatively wide bright line of light. If this misfortune has happened, it must be canceled again - without pressure!

Unfortunately, the problems don't end there. No material being cut is completely uniform - even in tomatoes there are softer and harder areas (although they are all much softer than blade steel). But not only tomatoes are cut with a knife! The difference in hardness between the parallel fibers of the wood and the resinous knot in it is already much greater. And the superiority of steel in hardness and mechanical strength over the mentioned knot is already noticeably less (especially if this steel is not from the highest category). But that's not all! There are many materials that contain inclusions even harder than the bulk of the material itself, and in some cases even harder than the steel of the blade. Take at least packing cardboard, and the most primitive sand contained in it. He gets there by simple carelessness - who will diligently clean source materials when making something so cheap! Or they can add it on purpose, especially if they sell the finished product by weight ...

If one of the above tests fails, repeat the last maintenance phase on leather or stone from 4 to 8 turns. The actual sharpening can take place every few months with certain stick bands and serves to restore the cutting edge. Each intersection of knife and beard results in a minimal bend in the thin cutting edge; a micron ridge is formed; removing or removing removes that crest bend. To avoid damaging the comb, never remove it immediately after shaving and keep the knife on for at least 24 hours.

Sand is crystalline silica, and grains of sand are much harder than even the highest quality knife steel. When the thin tip of the cutting wedge meets a grain of sand in its path, it cannot cut it and therefore pushes it aside. But at the same time, the blade itself experiences a lateral load, a lateral component appears in the reaction force, which can slightly bend the very top of the cutting wedge.

Matching leather razor strap

Whether it's the pro, the beginner, or the occasional wet razor, the right sling and clean finish make the difference in hair. There are various leather belts that differ in width, finish and finish. On some tapes natural coating still covered with paste and used for additional sharpening when normal leather is no longer sufficient. As an alternative, there are so-called paste bands, which are already processed by sharpening the paste and can be sharpened.

How better steel blade, the less the edge bends. With a very good blade and a very small grain of sand, the cutting edge will return to its place after bending. And if the steel is worse, or the grain of sand is larger, then the edge will remain slightly bent. Exactly the same thing happens when the blade takes force not quite in the plane of symmetry of the cutting wedge - for example, encountering a harder knot in the mass of wood, the fibers of which are directed at a different angle. Here, too, a lateral component of the load on the cutting edge appears.

Replace razor. Replace with pre-shave straps

Screw tension belts are a combination of towel belts and leather belts and provide both leather and sanding. The skin surface can be re-twisted as desired. One clamps the handle of the belt with his left hand and holds the knife on the right and provides the necessary tension. Knife Hold: The fingertips grip the handle and handle so that the razor can be rotated without jerky hand and knuckle movement. The cutting edge and back are always completely flat; light lifting of the back should be avoided as this will bend the edge and scratch the skin.

And the human hand never leads the blade exactly forward, so that the force falls on the cutting wedge strictly in the plane of its symmetry. In real cutting, the cutting edge is regularly subjected to random lateral loads, as a result of which it loses its straightness, and the wedge forming it loses its regular shape. Its top deviates from the plane of symmetry and after that, even with a perfectly correct cut, relatively soft material takes on the bending load. And the further the edge deviates, the greater this load becomes, as the bending moment increases - and as a result, the edge deviates even more. By itself, it will not return to its place - the cutting wedge has already lost its stable shape. Eventually, at a certain angle of bending, the tip of the wedge will simply break off, leaving a much wider surface in its place. The cutting efficiency will immediately decrease - in other words, the blade is pretty dull.

Knife movement: movement always occurs in the direction of the knife back; the rear guides move and the cutting edge is pulled. In this case, the belt must be taut, and the structure must be firm, but not pressed. Knife Rotation: When rotated, the razor will roll down the back without losing contact with the skin. This is done by turning the handle and grip between the fingertips; there is no movement of the hand. At the end of the belt, the cutting edge of the skin thus remains raised during the cutting edge. How often: there is no fixed correct rule here and depends on the individual degree of sharpness, material and technique.

Of course, the bending angle at which the tip of the cutting wedge breaks or bends depends on the properties of the steel and the quality of its heat treatment, but these are details. The essential thing is that the tip of the wedge of the cutting edge itself will never return to its original, stable position, which ensures optimal cutting quality.

As a rule, 10 trains per side are sufficient; with the so-called barbershop, whether the wet razor blade is sharp enough. Sharpen your razor - Grinding on belt pastes After use, the razor will not become sharp after a while with a clean setting. However, proper sharpening of your razor should only happen every few months, or at most after every 10 shaves. For this purpose, there are special belts that are already prepared with pastes or various pastes that can be applied by hand.

Pastes produce abrasion with small abrasive grains on the knife and serve to fine-tune the knife. Use the handle of the belt with your left hand and hold the knife on the right side and apply the necessary tension. The finished side points up. Holding the knife: The fingertips grasp the handle and handle so that the knife can be turned without jerky movement of the hands and knuckles. Turning the knife: when turning, the knife rolls over the back without losing contact with the skin. How often: Your knife should only be sharpened every few months or after every 10 shaves.

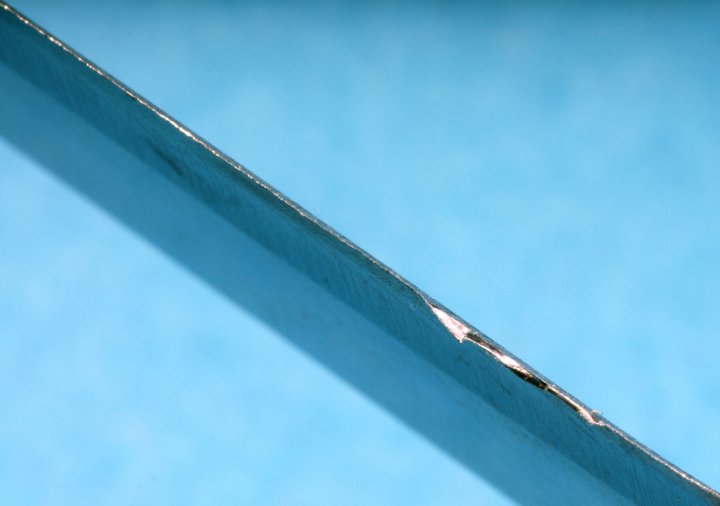

Another completely exceptional mechanism for loss of sharpness is damage to the cutting edge caused by knowingly misuse of the knife. For example, some users like to engage in demonstration cutting of nails. The nail, of course, is noticeably softer than even the worst blade - in any case, it is a third-rate alloy with a very low carbon content and without any heat treatment whatsoever. But their hardness is already comparable, after all, this is an iron product, moreover, it is thick, massive, especially in comparison with the thin cutting edge of the blade. Absolute strength is the sum of the relative strength (quality) of the material and its quantity. A thick linden log can break a thin plank of bog oak. So here - the cutting edge of a blade made of bad steel will simply crumble, hitting a slightly softer, but much more massive nail. A good blade, most likely, will cut a nail, but some of the steel will crumble out of its blade, and some will crumble, leaving a fair notch, which will be quite difficult to remove.

Unlike peeling, the knife should not be wrapped around the pastes too often when sharpening - please check the sharpness. Before starting, the stone must be watered. This the only way formation of sludge that contains abrasive particles. Between them, the stone must always be moistened with water again.

Grind the right lining to the knife

Most premium grinding stones come with holders. If they do not have a holder, this is also a common wooden plank. It doesn't have to be new, but it should be the plan. Because of the moisture, the stone sucks on the board and doesn't slip away.

Right angle for knife edge

Indicate the grinding angle with your thumb nail.

A serious person and a lover of knives will, of course, not cut nails with them. But it can simply by inadvertence accidentally hit the blade on something that the knife, in principle, cannot cut - for example, glass, ceramics (porcelain or faience, from which ordinary plates are made), metal, stone and so on. If a very sharply sharpened blade of excellent quality is dropped from a height of 15-20 cm with a blade perpendicular to the edge of the glass, then a notch visible even to the naked eye will remain on the blade.

Here the professional world is almost unanimous. The angle should be between 15 and 20 degrees. It touches the thumb nail under the blade back. There are also grinders that determine the angle. The more complex the knife blade, the sharper the angle will be.

My advice: don't overdo it and choose a corner that is subtly dim. The knife is then minimally less sharp - but keeps that sharpness longer. You must remember that the Japanese chef re-sharpened his knife every morning. These efforts should not be used at home. German or European knives should be ground with a more obtuse angle. If there are no exceptions, such as Nesmuk, Balbach.

Therefore, good advice right away: never quit your kitchen knives(and they, as a rule, have blades of not too hard steel and are sharpened quite thinly) into a metal or earthenware sink along with the rest of the dishes. Wash them carefully, holding them in your hands, dry them and set them aside. Do not throw them in the kitchen drawer either - there their blades will also be beaten against each other and against other appliances. Store knives separately in a wooden stand or on a wall with a magnetic holder.

Sharpen the blade in front of the knife. The knife should pass along the stone with a transverse edge. Whether you are describing 8 or a knife that just leads over the stone is irrelevant. It is important to evenly process all points of the cutting edge. When it reaches the tip, lift the blade slightly. Otherwise, the angle becomes too sharp. But you also notice it yourself.

If the side is now evenly grounded, move to the other side. Repeat the process with the same intensity. Before they start, you will be able to feel the degree at the forefront. Checking degree after grinding. When finished, you will also feel the degree on the other side. So turn the blade one more time and remove the comb with a few gentle strokes. Do the same again on the other side. Subsequently, on each side, the train to the ridge completely disappeared.

And throw away all the newfangled glass and porcelain cutting boards - cutting on them dulls knives instantly! Limit yourself to plastic or classic wooden boards. And do not ask the rhetorical question “why, then, are these boards made and sold, since they spoil knives?” Apparently, for this they make and sell in order to spoil. To keep the knife as short as possible, so that you have to buy new ones more often. Yes, and the wooden board itself, if it is good, can last for years, and most people will break glass or porcelain boards within a few months, purely by accident, dropping it from the height of the cutting table onto the tiled floor. This is where the business goes.

And all the stories, stories and advertisements about "self-sharpening" blades can be safely attributed to the realm of fantasy, and also completely unscientific. The effect of "self-sharpening" a real knife is only that you have to sharpen it yourself, and no one will do it for you. So, you need to figure out how to do it right.

How to sharpen a knife?

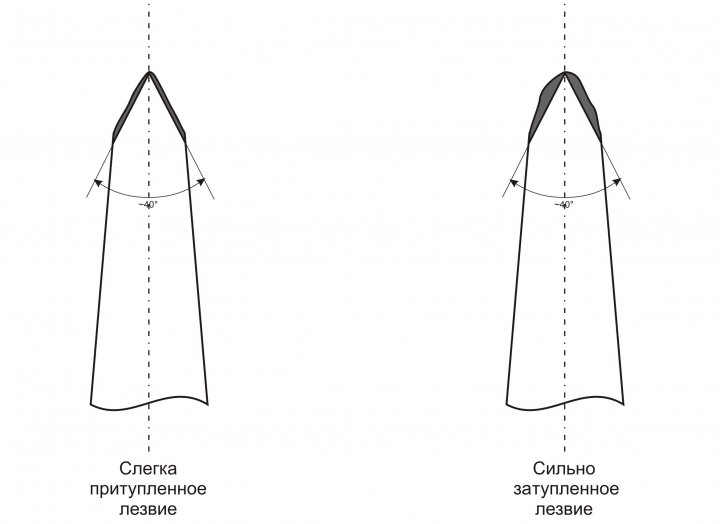

To return the cutting edge to the correct wedge-shaped profile, you need to profile it again by grinding off excess material. And since you have to grind quite hard and wear-resistant steel, with a fairly running blade, you have a lot of work to do, even if you have necessary tool and skills.

Does it make sense to sharpen a knife on an electric grinding wheel? I would absolutely not recommend doing this. Each steel has a certain heat treatment mode. Uncontrolled heating as a result of high-speed grinding, reaching many hundreds of degrees at the cutting edge itself, can irreversibly damage the blade. And periodic dipping into water during sharpening is not able to prevent this.

What to sharpen? On the bars. Which ones and how to choose them is a topic for a separate article. For now, I’ll just say: don’t skimp on bars! Especially if you have a lot of knives or if they are quality expensive knives. A bad knife can somehow be sharpened on a bad bar. But on a good one, it is much easier and better to do this, although a bad knife will not become good from this anyway. Sharpening a good knife on a good whetstone is a pleasure and a great way to relax and relieve stress. But sharpening (or rather, attempts to sharpen) an expensive branded knife on a bad bar is already masochism, and even a mockery of a noble blade.

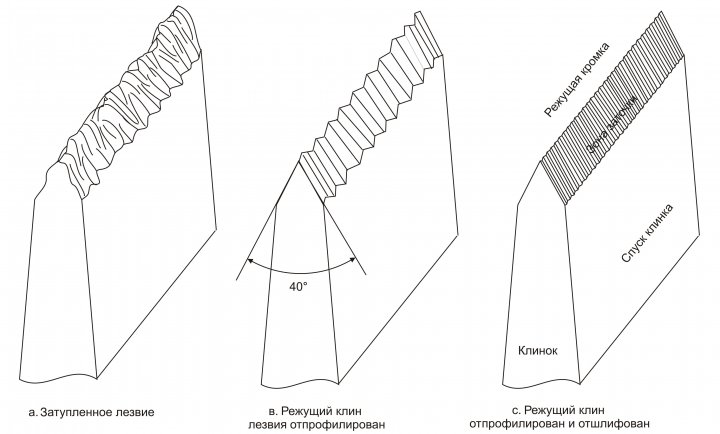

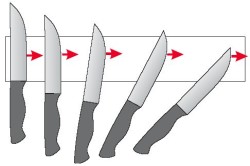

First, a few words about the direction of sharpening. It is imperative to sharpen so that the direction of grinding at each point of the blade is perpendicular to the cutting edge (or as close as possible to this). Each abrasive material and tool leaves its marks in the form of scratches on the polished object. Their individual grains are applied, with which the mass of abrasive material is filled. The finer the grains of the abrasive, the thicker they are deposited in the mass of the material, and the less deep and more frequent scratches they leave. If the scratches left by the abrasive are directed perpendicular to the cutting edge of the blade, then their combination forms on the cutting edge something like a nail file with almost microscopic (although clearly visible under a strong magnifying glass) teeth, which, when cut, will “saw” the material being cut, increasing the cutting efficiency and aggressiveness.

If you grind the blade along the blade, then the micro-scratches will be directed accordingly. When cutting, they act as points of concentration of lateral loads. It is on them that the thin tip of the cutting wedge breaks off very easily even with the slightest lateral load, leaving the blade blunter than before sharpening. Yes, and there are no “microfiles” after such sharpening - the knife shaves the hair on the forearm willingly, but the rope or sinewy meat cuts much worse than properly sharpened. And the fact that such sharpeners are produced and sold is again more about sales, and not about sharpening.

To achieve perfect perpendicularity between the cutting edge and the micro-scratches left by the abrasive during manual sharpening, of course, will not succeed. After all, the blade must be simultaneously driven with the blade along the bar and fed in the longitudinal (relative to the blade itself) direction - so that while the blade reaches the end of the bar, it has time to walk along it with the entire length of the blade. Hence the conclusion: in order for the micro-scratches left by the bar to be as close as possible to the perpendicular to the cutting edge, the bar must be long enough. Good sharpening results are provided by a bar that is at least one and a half times longer than the blade, and preferably twice. The longer, the better! back side medals - a larger bar costs more.

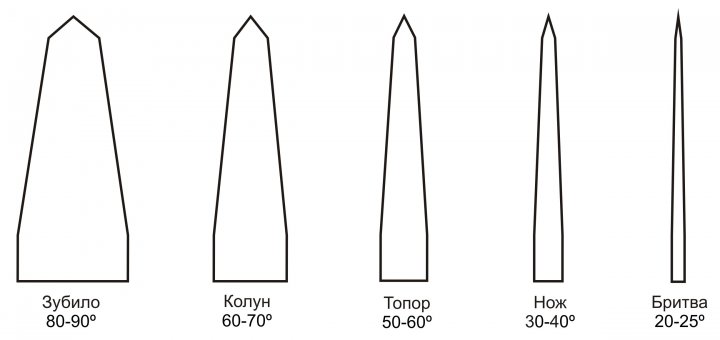

Now let's talk about the optimal sharpening angle. Of course, it depends on the nature and application of the tool being sharpened. The thinner the wedge, the better and more efficiently it cuts - precisely because of the greater concentration of cutting force on its tip. But at the same time, it is also easier to deform this very wedge - again, due to the huge concentration of resistance of the material being cut on it. There are no blades that are both strong and sharp, cut well and withstand heavy loads - or one or the other. Try shaving with a chisel or cutting a nail with a razor! The optimal ratio between cutting efficiency and sharpening strength depends primarily on what exactly and how we are going to cut. The harder the material being cut, the stronger the blade must be, the more steel must be behind the cutting edge to support it and help withstand the loads concentrated on it.

Cutting speed also plays an important role. Shaving hair differs from cutting wood not only in the hardness and strength of the material being cut, but also in the speed with which the blade interacts with it. But it is known that a high cutting speed requires more effort, and, therefore, entails a greater resistance force. This means that the cutting wedge must be stronger.

The level of side loads that inevitably accompany work also matters. No one ever “breaks out” a razor stuck in the hair, it even sounds somehow ridiculous. Well, an ax driven into a solid tree is “broken out” all the time. Therefore, if we want as much of the cutting wedge as possible to “break out” of the tree along with the ax, and as small as possible to break out of the ax blade and remain stuck in the tree, then the cutting wedge again needs to be made stronger, which means thicker. It is necessary to do this even to the detriment of the sharpness and efficiency of the cut - the blade, which is strongly deformed with each blow, will instantly lose both one and the other. Therefore, the sharpness of a razor is far from being the same as the sharpness of an axe.

It is also impossible to consider the optimal angle of sharpening the blade in isolation from the quality of the blade. Here, the hardness and mechanical strength of steel are included in the calculation, which, generally speaking, is far from the same thing. Cheap medium carbon steel can also be hardened to extreme hardness, only it will become brittle like glass and will easily crumble. Of two blades designed for the same job, the one made of better steel can be sharpened at a sharper angle, thereby increasing its cutting efficiency. A blade made of the worst steel has to be sharpened at a more obtuse angle in order to compensate for the lower mechanical strength of the material with a large amount of it in the most loaded place - on the cutting edge and immediately behind it.

If speak about numerical values sharpening angle of the blade (for a blade made of steel of the appropriate quality and properly heat-treated), then I would suggest the following approximate values for the optimal full angle sharpening:

Chisel - 80-90º, depending on what we are going to cut - steel cable, soft iron wire or aluminum sheets.

Ax - 50-70º, again, depending on the tasks. For chopping wood, you need a thicker wedge with a more obtuse angle. If this is a lumberjack or tourist, universal or butcher's ax, then it is somewhat thinner so that it cuts better, but the blade was still strong enough. And if this is a carpenter's ax, designed, for example, for precise hewing of a log hut “into a castle”, then it is even thinner, almost like a knife.

Knife - 30-40º, kitchen can be sharpened to a smaller angle, tourist - to a larger one.

Razor - 20-25º. I know that about the same number of people shave with dangerous razors that require sharpening today, as log huts amuse. But this does not change the essence of the matter.

As already mentioned, in order to properly form the cutting wedge, you need to grind across the cutting edge of the blade. But which way? Or is it all the same?

Steel consists of small crystals of very hard iron carbide - cementite, which are interspersed in a matrix of relatively soft iron containing a small amount of carbon. The cutting abrasive grains have a hardness comparable to that of cementite. Therefore, they easily cut the soft matrix of steel, and the cementite crystals are already difficult to cut. Or they don’t cut at all, but pull them along, moving them in a soft matrix or even tearing them out of it. When steel particles are pulled in the direction of the cutting edge, a so-called burr inevitably forms on it, which is formed largely from these crystals torn from the matrix - in other words, from a metal with a hopelessly broken crystal structure and completely useless from the point of view of cutting. Useless precisely because with a broken structure, its mechanical strength becomes simply miserable, in most cases such a burr easily breaks off at the first cut. Well, why then, you ask, sharpen?

I have long noticed that the vast majority of people, when sharpening, for completely unknown reasons, lead the blade along the bar with the butt forward. At the same time, the edge of the steel at the cutting edge is pulled out, forming an unnecessary burr, and the steel is “loosened”, pulling hard cementite crystals from the soft matrix. But you need to do just the opposite - to drive the blade along the bar with the blade forward in order to press these crystals, compacting the steel, and preventing excessive burr formation.

If you drive the blade being sharpened along the bar with the blade forward, as if stricter with a bar, then a burr will also form, but it will be incomparably smaller. The size of the burr depends on many reasons: the quality of the steel itself, its heat treatment, the quality and degree of graininess of the abrasive material, the cleanliness of the abrasive surface, the speed of the mutual movement of the blade and the abrasive, the pressure force on the blade, and so on. In practice, it will never be possible to get rid of the burr completely and completely, processing the cutting edge perfectly, as in the figure. Our task is this: firstly, to try to form a burr of the smallest possible size, and secondly, in the process of sharpening, further reduce it as much as possible. Then the burr that breaks off already at the first cut will leave behind a sufficiently narrow surface so that it does not interfere with the concentration of effort at the top of the cutting wedge.

Finishing

When the cutting wedge of the blade is already properly formed, it remains only to grind it to a certain degree of smoothness, or, in technical terms, the purity of the processing. Therefore, in the process of sharpening, you have to change the bar to a smaller one, and then to an even smaller one. What should be the bar for the final finishing of the blade? It depends again on the intended use of it! Properly drawn forming surfaces of the cutting wedge will always carry scratches from processing on abrasive material. They will never completely disappear, and their dimensions - width and depth - will depend on what grit we finish the blade on.

The larger the abrasive grains on which we finish sharpening, the larger the teeth on the cutting edge will be and the more they will protrude above the "hollows" between them. This means that the concentration of force on the tips of the teeth will be high, and the blade will cut more aggressively. But the load on individual teeth will also be large, which in turn will lead to their accelerated chipping - that is, to a loss of blade sharpness. This means that a blade finished with a coarse-grained abrasive will cut more efficiently and aggressively, but will lose sharpness faster. And vice versa - the cutting edge of the blade, finished on a fine-grained abrasive, consists of small teeth. The cutting force on such a blade is spread out more evenly, which reduces the efficiency and aggressiveness of the cut. But at the same time, this reduces the load on individual cloves - now they are not so easy to crumble! This means that the blade will keep sharpening longer, albeit at the expense of some decrease in the efficiency and aggressiveness of the cut.

In turn, the desired aggressiveness of the cut depends on what exactly we are cutting. If it is something very fibrous, such as ropes or sinewy meat, then the microsaw will noticeably facilitate the work of the blade. And if we shave, plan pencils or chop trees, then the blade collides with the material being cut strictly across its cutting edge, and the microsaw will not help here. Therefore, it is worth making it as small as possible, finishing the blade on a thinner abrasive and thus increasing its strength.

Theoretically, there are two types of cut. One is when the blade enters the material being cut at a very high feed along the cutting edge and with an incomparably smaller lateral advance. So the scythe cuts grass, the knife cuts very ripe tomatoes. So you can quite sensitively cut your finger with the edge of an ordinary sheet of paper. Let's conditionally call this type of cut "sawing". Another type is when the blade strikes the material in a direction strictly across the cutting edge with little feed along it. So the razor cuts the hair, the knife of a mechanical mower cuts the grass. So the plane blade cuts wood, and the shredding knife cuts cabbage. Let's conditionally call this type of cut "planing".

Unlike a razor, a scythe, or a planer, a knife is a relatively versatile cutting tool. He performs a wide variety of cutting activities, among which pure "sawing" and pure "planing" are extremely rare. The vast majority of real cuts consists of "sawing" and "planing" in various proportions.

If the intended use of the knife involves a predominance of “sawing” in cuts (cutting meat into slices, cutting ropes or car seat belts, applying cutting blows, etc.), then a blade finished with a rather coarse-grained abrasive will work better. And if “planing” prevails in cuts (peeling potatoes, deboning meat, sharpening pencils, planing wood), then a blade finished on the finest possible abrasive almost to mirror shine. In addition, such a blade will keep sharpening much longer.

Afterword

All of the above is the basics of sharpening, its physical theory. Range practical application these foundations are in fact almost as wide as the spectrum of practical manifestations of the law of universal gravitation. No one will ever be able to find pre-calculated, academic solutions to problems for all occasions - there is nothing to dream about. This means that you have to be flexible in thinking and look for solutions to emerging issues on the fly, along the way. Sometimes the solution will be successful, and other times not so much.

Here is an example. I always try to finish my knife blades as smoothly as possible, using the finest abrasive possible. I do this for several reasons. The first is capabilities, as I have a very large and diverse collection of tools for manual sharpening(including those, the blade finish with which it is difficult to call it anything other than pampering and snobbery - but sometimes it's nice to just sit and have fun, and experiment on occasion). The second reason is that I always use blades of excellent quality, made of very good steels and heat treated accordingly. Therefore, I always try to sharpen them at as small an angle as possible so that they cut as efficiently as possible, even at the expense of the strength of the blade. And the third - I treat my knives with care, I never allow even the smallest carelessness, and therefore the strength of the blade is not such an important and desirable feature for me. Well, and besides, I always like to have a very sharp knife on hand - which means I strive to sharpen the blade in such a way that it keeps sharpening as long as possible. But even with all that in mind, I've had plenty of opportunity to see that sometimes (albeit rarely) my approach to sharpening isn't quite right. Sometimes you would like to have a blade sharpened more aggressively in your hand - even if the sharpening would only be enough for a few cuts. For example, to quickly cut the seat belts in an accident car. You can never foresee everything: the decision on how to sharpen your knives is yours.

It would be necessary to talk about what kind of abrasive (diamond, natural, ceramic or some other) the blade should be sharpened, and on which one - to finish it completely. We will return to the question of what abrasives are in general, what properties each of them has and for what purposes it should be used, we will return later, in another article.

Text and illustrations: Sergey Mitin

It is believed that every man should know how to sharpen a knife to razor sharp. But for all the seeming simplicity of the operation, not everyone owns this art. And it's not about the ability to hold the blade at the right angle, but knowledge in the strictest confidence is passed down from generation to generation. In order to properly sharpen a knife, you need to know something about the knife itself, and about the sharpening tool, and about the materials from which our knife is made. Below we will tell our readers about all this. Well, and, of course, we will reveal the secrets of the skill of sharpening.

To safely use a knife, it must be properly sharpened.

A few words about knives

For a good owner, all knives in the house should always be sharp, like a razor. It has been so for a long time. Therefore, many men try to follow the tradition, regularly spending a lot of time trying to achieve unprecedented sharpness from a bread knife.

A sharp knife speeds up the process of working in the kitchen.

But sharpening should be considered not only as a tribute to some abstract traditions. Any cook will confirm that a sharp knife speeds up the cooking process several times. In addition, it is easy to work with him, the hand does not get tired of chopping meat or vegetables.

And a razor-sharp knife makes working in the kitchen safe. Yes exactly! A dull blade can move to the side, after which the hand slips. And, at best, everything will cost a fright. At worst, you can seriously injure yourself or catch one of those present nearby. After all, even a knife that does not have a razor sharpness remains sharp, especially its tip.

Before you start sharpening knives, you should find out the hardness of the steel from which the blade of each of them is made. The fact is that the angle at which sharpening will be carried out depends on the hardness of the steel. This parameter is measured in special units, and hardness can only be determined in laboratory conditions using special equipment. The standard value for most knives is 45-60 Rockwell Hardness Units (HRC). Both soft and hard steel will have to be sharpened all the time, because the first will constantly wear out, and the second will crumble.

Why is the knife dull?

The question is serious. If the steel has the right hardness, then why does the knife become dull and not retain its sharpness, like a razor?

The effort when cutting products is a sign of knife sharpening.

There are several reasons. First: no matter how hard the material is, in the process of use it is subject to external influences. Under the influence of the friction force, microscopic metal particles are detached from the main body, the sharp edge is gradually destroyed. In addition, it is not possible to constantly hold the knife in the so-called "ideal position", when the cutting edge of the knife is in contact with the surface at an optimal angle. The resulting loads have a destructive effect on the metal. As a result, razor sharpness is lost.

But since this process can be called microscopic, it is not possible to immediately understand whether the knife has lost its sharpness, like a razor. The first signal may be the increasing force that has to be applied to cut something with such a knife. The loss of sharpness can also be determined by eye: blunt areas on the blade look like polished, they have a characteristic sheen.

So it's time to sharpen the blade like a razor. To make the process as efficient as possible, you should choose the right tool.

Choosing a sharpening tool

In order to bring the blade to the required sharpness, you should choose the right material for sharpening it. It could be:

- whetstone;

- musat;

- electric grinding machine;

- abrasive machine;

- grinding machine;

- mechanical sharpener;

- electric sharpener.

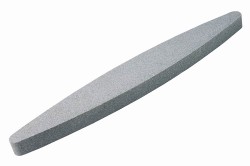

To sharpen knives, you can use a special bar.

Let's look at each of them separately. The whetstone is an ancient tool used to make a knife as sharp as a razor. Experienced craftsmen know that in fact there are many bars, with different grain sizes (the smallest abrasive particle that makes up the bar itself), different hardness and density. In order to sharpen the blade with high quality and then grind it, you need two bars. One with large grains, the other with small grains. You can determine this by special markings, but you can also see the difference between such bars by eye.

Musat, as well as a mechanical sharpener, is a kitchen accessory. With its help, knives are not sharpened, but rather corrected, removing micro-chips and returning the sharpness of razors for a while. This time is short, because the musat and the sharpener do not affect the steel at a sufficient level.

An electric sharpener saves us from applying physical effort to sharpen the blade, but it is also not able to return it to razor sharpness.

Special sharpening and grinding machines are able to quickly return to the knife its cutting properties, but the trouble is that it is expensive and dangerous to keep such equipment at home. The machine produces a lot of dust and noise, while taking a decent amount of electricity. But with its help, you can give any of the knives any sharpness for a short time and without much effort.

But experts advise not to take up work on grinding machines, if there is no experience at least as a toolmaker. You can hopelessly ruin the blade on a knife by overheating it or sharpening it at the wrong angle.

How to sharpen

An electric sharpener is very convenient for sharpening knives.

So, we come to the most important question: how to properly sharpen so that the blade reaches razor sharpness?

The main thing is to be patient. Steel processing takes time, the more we want to achieve, the more time it will take. In order for the knife to be operated like a razor, it will take at least 30 minutes of hard work.

Consider the classic way of sharpening with a whetstone. The abrasive should be placed on flat surface(table or workbench in the workshop) and place a rough cloth or fleecy material under it. This will facilitate the work process, since the bar will not fidget and you will not have to hold it with your hand all the time.

Knives are sharpened by making passes along the entire length of the abrasive. In this case, it is necessary to ensure that the cutting edge of the blade is constantly in a perpendicular position with respect to the longitudinal axis of the bar. In practice, it looks like this: the blade has a curved surface, so when moving, the knife should be turned so that each of its sections is at right angles to the axis of the abrasive material.

In the process, it is important to keep the metal at the same angle in relation to the sharpener.

It should be equal to 20-25 degrees, since this is the optimal value for the cutting edge. Knives intended for chopping meat should be sharpened at a large angle. By keeping the angle of metal processing constant, you can sharpen literally any steel to an incredible sharpness.

The blade should be carried along the entire length of the bar, and it is not at all necessary to apply great efforts. Excessively strong pressure will lead to the destruction of the material and the violation of the integrity of its surface. Because of this, the sharpening process may be delayed.

When a thin uneven edge appears on the knife, you can proceed to the next step and change the rough bar to a smaller one. Having achieved uniform sharpening, you should fix the result obtained by grinding.

knife grinding

This is the final step in the knife sharpening process, resulting in a razor-sharp edge. For work, a special grinding block with a very fine grain is used. It feels like a velvety surface to the touch, but don't be deceived: it can sharpen the blade as sharply as the finest razors in the world.

What is grinding for? It not only gives the cutting edge desired properties but also reinforces them. A polished metal surface is not as susceptible to destruction as a regular one. Thanks to this, the sharpness will remain for a long time.

In the process of grinding, you should follow the same principles as when sharpening. The movements must be uniform and measured, the blade must always be perpendicular to the axis of the bar, the angle of inclination of the metal to the abrasive must also be constant. And there is no need to exert excessive effort, because the metal will level out layer by layer. Razor sharpness will be the result.

It remains to add that you can learn all this, but it will take some practice. But thanks to the acquired skills, each owner will always be able to keep the knives in his house sharply sharpened.

Chicken in kefir - recipes for marinated, stewed and baked poultry for every taste!

Simple Chicken Recipe in English (Fried) Recipes in English with translation

Chicken hearts with potatoes: cooking recipes How to cook delicious chicken hearts with potatoes

Recipes for dough and fillings for jellied pies with mushrooms

Stuffed eggplant with chicken and mushrooms baked in the oven with cheese crust Cooking eggplant stuffed with chicken