When dinner was over, Iren ordered whom to sing, to whom he asked questions that required reflection and ingenuity, such as: “Who is the best among husbands?” or “What is the act of such and such a person?” So from the very beginning of their lives they were accustomed to judge the merits of fellow citizens, for if the one to whom the question was addressed “Who is a good citizen?” Who deserves blame? , did not find what to answer, this was considered a sign of nature sluggish and indifferent to virtue. In the answer, it was supposed to name the reason for this or that judgment and give evidence, putting the thought into the shortest words. The one who spoke out of place, not showing due diligence, Iren punished - he bit his thumb. Often, Iren punished boys in the presence of old people and authorities, so that they would be convinced of how justified and fair his actions were. During the punishment he was not stopped, but when the children dispersed, he held the answer if the punishment was stricter or, on the contrary, softer than it should have been.

And the good fame and dishonor of the boys was shared with them by their beloved. It is said that when one day a boy, having grappled with a comrade, suddenly got scared and screamed, the authorities imposed a fine on his lover. And, although the Spartans allowed such freedom in love that even worthy and noble women loved young girls, rivalry was unfamiliar to them. Not only that: common feelings for one person became the beginning and source of mutual friendship of lovers, who united their efforts in an effort to bring their loved one to perfection.

19. Children were taught to speak in such a way that in their words caustic wit was mixed with grace, so that short speeches caused lengthy reflections. As already mentioned, Lycurgus gave the iron coin great weight and negligible value. He acted completely differently with the “verbal coin”: under a few mean words, a vast and rich meaning should have been hidden, and by forcing the children to be silent for a long time, the legislator elicited accurate and accurate answers from them. For just as the seed of people who are immensely greedy for intercourse is mostly fruitless, so the intemperance of the tongue gives rise to empty and stupid speeches. Some Athenian scoffed at the Spartan swords - they are so short that they are easily swallowed by magicians in the theater. “But with these daggers we perfectly get our enemies,” King Agid objected to him. I find that the speech of the Spartans, with all its external brevity, perfectly expresses the very essence of the matter and remains in the minds of the listeners.

Lycurgus himself apparently spoke little and aptly, as far as one can judge from his sayings that have come down to us. So, to a man who demanded the establishment of a democratic system in Sparta, he said: “First, you establish democracy in your house.” Someone asked why he made the sacrifices so modest and modest. “So that we never cease to honor the deity,” replied Lycurgus. And here is what he said about competitions: “I allowed fellow citizens only those types of competitions in which you do not have to raise your hands.” It is reported that in letters he answered his fellow citizens no less successfully. “How can we avert the enemy’s invasion from ourselves?” - "Remain poor, and let no one try to become more powerful than another." About city walls: "Only that city is not without fortifications, which is surrounded by men, and not by bricks." It is difficult, however, to decide whether these letters are genuine or forged.

20. The following statements testify to the disgust of the Spartans for lengthy speeches. When someone began to talk about an important matter, but inappropriately, Tsar Leonid said: “Friend, all this is appropriate, but in a different place.” Lycurgus' nephew Harilaus, when asked why his uncle issued so few laws, replied: "Those who manage with a few words do not need many laws." Some people scolded the sophist Hecataeus, because, invited to a common meal, he kept silent throughout the dinner. “Whoever knows how to speak, knows the time for this,” Archidamid objected to them.

And here are examples of sharp, but not without elegance, memorable words, which I have already mentioned above. Some rogue pestered Demarat with absurd questions and, by the way, kept wanting to know who was the best of the Spartans. “The one who is least like you,” Demarat finally said. Agid, hearing the praises of the Eleans for the excellent and fair organization of the Olympic Games, remarked: “It’s really a great thing to do justice once every four years.” A foreigner, to show his friendly feelings, told Theopompus that among his fellow citizens he is called a friend of the Laconians. “It would be better for you to call yourself a friend of fellow citizens,” answered Theopompus. The son of Pausanias Plistoanakt said to the Athenian speaker, who called the Spartans ignoramuses: “You are right - of all the Greeks, we alone did not learn anything bad from you.” Archidamid was asked how many Spartans there were. “Enough, friend, to repel the villains,” he assured. From the jokes of the Spartans, one can also judge their habits. They never chatted in vain, never uttered a word that did not have a thought behind it, one way or another worthy of thinking about it. The Spartan was called to listen to how they imitate the song of a nightingale. “I heard the nightingale himself,” he refused. Another Spartan, reading the epigram:

remarked: "And rightly so: it was necessary to let her burn to the ground." A young man said to a man who promised to give him roosters that fight to the last breath: “Keep them for yourself, and give me those that beat the enemy to the last breath.” Another young man, seeing people who emptied their intestines while sitting on a toilet seat, exclaimed: “I wish I never had a chance to sit in such a place that it is impossible to give way to an old man!” Such are their sayings and memorable words, and some, not without reason, assert that to imitate the Laconians means to attach one's soul to philosophy rather than to gymnastics.

21. Singing and music were taught with no less care than the clarity and purity of speech, but even in the songs there was a kind of sting that aroused courage and compelled the soul to enthusiastic impulses to action. Their words were simple and unsophisticated, the subject - majestic and didactic. These were mainly glorifications of the happy fate of those who fell for Sparta and reproaches to cowards doomed to drag out life in insignificance, promises to prove their courage or, depending on the age of the singers, boasting of it. It would be useful to place here, as an example, one of these songs. On holidays, three choirs were composed - old men, husbands and boys. The old people sang:

Men in their prime picked up:

And the boys finished:

In general, if anyone reflects on the works of the Laconian poets, some of whom have survived to this day, and restores to memory the marching rhythms of melodies for the flute, to the sounds of which the Spartans marched on the enemy, he will perhaps admit that Terpander and Pindar were right in finding connection between courage and music. The first says of the Lacedaemonians thus:

And Pindar exclaims:

Both depict the Spartans as both the most musical and the most warlike people.

said the Spartan poet. Not without reason, before the battle, the king sacrificed to the Muses - in order, it seems to me, that the soldiers, remembering the upbringing they received and the sentence that awaits them, boldly walked towards danger and performed feats worthy of being preserved in speeches and songs.

22. During the war, the rules of behavior for young people were made less severe: they were allowed to take care of their hair, decorate their weapons and clothes, mentors rejoiced at seeing them like war horses that proudly and impatiently dance, snort and rush into battle. Therefore, although the boys began to look after their hair as soon as they were children, they especially diligently anointed and combed it on the eve of danger, remembering the words of Lycurgus about hair, that they make beautiful hair even more plausible, and ugly - even more terrible. On campaigns, gymnastic exercises became less strenuous and tiring, and in general at this time the young men were asked less strictly than usual, so that on the whole earth for the Spartans alone, the war turned out to be a rest from preparation for it.

When the construction of the battle line ended, the king, in front of the enemy, sacrificed a goat and gave a sign to everyone to crown himself with wreaths, and the flutists ordered Kastorov to play the tune and at the same time he tightened the marching paean. The spectacle was majestic and formidable: the warriors advanced, stepping in accordance with the rhythm of the flute, firmly holding the line, not experiencing the slightest turmoil - calm and joyful, and their song led. In such a state of mind, probably, neither fear nor anger has power over a person; unshakable steadfastness, hope and courage, as if bestowed by the presence of a deity, gain the upper hand. The king went to the enemy, surrounded by those of his people who deserved the wreath by winning the competition. It is said that at the Olympic Games one Laconian was given a large bribe, but he refused the money and, having gathered all his strength, defeated the enemy. Then someone said to him: “What is the benefit to you, Spartan, from this victory?” “I will take a place in front of the king when I go into battle,” the winner replied smiling.

The Spartans pursued the defeated enemy only as much as was necessary to secure victory for themselves, and then immediately returned, considering it ignoble and contrary to the Greek custom to destroy and exterminate those who stopped the fight. This was not only beautiful and generous, but also beneficial: their enemies, knowing that they killed those who resisted, but spared those who retreated, found it more useful for themselves to flee than to remain in place.

23. Lycurgus himself, according to the sophist Hippias, was a man of proven militancy, a participant in many campaigns. Philostephan even attributes to him the division of the cavalry into ulama. Ulam under Lycurgus was a detachment of fifty horsemen, built in a quadrangle. But Demetrius of Phaler writes that Lycurgus did not touch on military affairs at all and established a new political system during the time of peace. And it is true that the idea of the Olympic Truce could, apparently, belong only to a meek and peace-loving person. However, as Hermippus says, others argue that at first Lycurgus had nothing to do with all this and had nothing to do with Ifit, but arrived at the games by accident. There he heard a voice behind him: someone reproved him and marveled that he did not incline fellow citizens to take part in this general celebration. Lycurgus turned around, but the speaker was nowhere to be seen, and, considering what happened to be a divine sign, he then only joined Ifit; together they made the festival more magnificent and glorious, gave it a reliable foundation.

24. The upbringing of the Spartan continued into adulthood. No one was allowed to live the way he wanted: as if in a military camp, everyone in the city obeyed the strictly established rules and did what was assigned to them from the affairs useful to the state. Considering themselves belonging not to themselves, but to the fatherland, the Spartans, if they had no other assignments, either watched the children and taught them something useful, or themselves learned from the old people. After all, one of the benefits and advantages that Lycurgus brought to his fellow citizens was the abundance of leisure. They were strictly forbidden to engage in craft, and in the pursuit of profit, which required endless labor and trouble, there was no need, since wealth had lost all its value and attractive power. The helots cultivated their land, paying the appointed tax. One Spartan, being in Athens and having heard that someone was condemned for idleness and the condemned returned in deep despondency, accompanied by friends, also saddened and distressed, asked those around him to show him a man to whom freedom was imputed as a crime. That's how low and slavish they considered all manual labor, all sorts of worries associated with profit! As was to be expected, litigation disappeared along with the coin; and need and excessive abundance left Sparta, their place was taken by the equality of prosperity and the serenity of complete simplicity of morals. The Spartans devoted all their free time from military service to round dances, feasts and festivities, hunting, gymnasiums and forests.

25. Those under thirty years of age did not go to the market at all and made the necessary purchases through relatives and lovers. However, even for older people it was considered shameful to constantly push around in the market, and not spend most of the day in gymnasiums and forestries. Gathering there, they sedately talked, not mentioning a word about either profit or trade - the hours flowed in praise of worthy deeds and censures of bad ones, praises, combined with jokes and ridicule, which inconspicuously exhorted and corrected. And Lycurgus himself was not overly harsh: according to Sosibius, he erected a small statue of the god of Laughter, wishing that a joke, appropriate and timely, would come to feasts and similar meetings and become a kind of seasoning for the labors of every day.

In a word, he taught fellow citizens that they did not want and did not know how to live apart, but, like bees, were inextricably linked with society, everyone was closely united around their leader and wholly belonged to the fatherland, almost completely forgetting about themselves. in a fit of inspiration and love for glory. This way of thinking can be discerned in some of the sayings of the Spartans. So Pedarit, not chosen among the three hundred, went away, beaming and rejoicing that there were three hundred better people in the city than he. Polystratides and his comrades arrived as an embassy to the commanders of the Persian king; they inquired whether they were on private business or on behalf of the state. “If everything goes well - on behalf of the state, if not - on a private matter,” answered Polystratides. Several citizens of Amphipolis, who ended up in Lacedaemon, came to Argyleonida, the mother of Brasidas, and she asked them how Brasidas died and whether his death was worthy of Sparta. They began to extol the deceased and declared that there was no second such husband in Sparta. "Don't talk like that, strangers," said the mother. “It is true that Brasidas was a worthy man, but there are many more remarkable ones in Lacedaemon.”

26. As already mentioned, Lycurgus appointed the first elders from among those who took part in his plan. Then he decided to replace the dead every time to choose from citizens who have reached sixty years of age, the one who will be recognized as the most valiant. There was probably no greater competition in the world and no victory more desirable! And it’s true, because it was not about who is the most agile among the agile or the strongest among the strong, but about who among the kind and wise is the wisest and best, who, as a reward for virtue, will receive the supreme one until the end of his days - if here this word is applicable, - power in the state, will be master over life, honor, in short, over all the highest blessings. The decision was made as follows. When the people gathered, the special elected ones closed themselves in the house next door, so that no one could see them, and they themselves could not see what was happening outside, but would only hear the voices of those assembled. The people in this case, as in all others, decided the matter by shouting. Applicants were not introduced all at once, but in turn, in accordance with the lot, and they silently passed through the Assembly. Those who were locked up had signs on which they noted the strength of the scream, not knowing to whom they were shouting, but only concluding that the first, second, third, in general, the next applicant had come out. The chosen one was declared the one to whom they shouted more and louder than others. With a wreath on his head, he went around the temples of the gods. He was followed by a huge crowd of young people, praising and glorifying the new elder, and women who sang of his valor and proclaimed his fate happy. Each of his relatives asked him to eat, saying that the state was honoring him with this treat. Having finished his rounds, he went to a common meal; the established order was not violated in any way, except for the fact that the elder received the second share, but did not eat it, but put it off. His relatives stood at the door, after dinner he called one of them, whom he respected more than others, and, handing her this share, said that he was giving away the award that he himself had received, after which the rest of the women, glorifying this chosen one, escorted her home.

27. No less remarkable were the laws concerning burial. Firstly, having done away with all kinds of superstition, Lycurgus did not interfere with burying the dead in the city itself and placing tombstones near the temples, so that young people, getting used to their appearance, would not be afraid of death and would not consider themselves defiled by touching a dead body or stepping over the grave. Then he forbade anything to be buried with the deceased: the body was to be interred wrapped in a purple cloak and entwined with olive green. It was forbidden to inscribe the name of the deceased on the gravestone; Lycurgus made an exception only for the fallen in the war and for the priestesses. He set a short period of mourning - eleven days; on the twelfth, a sacrifice was to be made to Demeter and an end to sorrow. Lycurgus did not tolerate indifference and inner relaxation, he somehow combined the necessary human actions with the assertion of moral perfection and the condemnation of vice; he filled the city with many instructive examples, among which the Spartans grew up, which they inevitably encountered at every step, and which, serving as a role model, led them along the path of good.

For the same reason, he did not allow to travel outside the country and travel, fearing that foreign customs would not be brought to Lacedaemon, they would not begin to imitate someone else's, disorderly life and a different form of government. Moreover, he drove out those who flocked to Sparta without any need or definite purpose - not, as Thucydides claims, that he was afraid that they would not adopt the system he had established and would not learn valor, but rather, fearing how if these people themselves did not turn into teachers of vice. After all, along with strangers, other people's speeches invariably appear, and new speeches lead to new judgments, from which many feelings and desires are inevitably born, as opposed to the existing state system as wrong sounds are to a well-coordinated song. Therefore, Lycurgus considered it necessary to guard the city more vigilantly from bad morals than from an infection that could be brought from outside.

28. In all this there is not a trace of injustice, for which some blame the laws of Lycurgus, believing that they instruct quite enough in courage, but too little in justice. And only the so-called cryptia, if only she, as Aristotle claims, is a Lycurgus innovation, could inspire some, including Plato, with a similar judgment about the Spartan state and its legislator. That's how cryptos happened. From time to time, the authorities sent young people, who were considered the most intelligent, to roam the neighborhood, providing them with only short swords and the most necessary food supply. During the day they rested, hiding in secluded corners, and at night, leaving their shelters, they killed all the helots they captured on the roads. Often they went around the fields, killing the strongest and strongest helots. Thucydides in the Peloponnesian War tells that the Spartans chose helots who distinguished themselves by their special courage, and those with wreaths on their heads, as if preparing to gain freedom, visited temple after temple, but a little later they all disappeared - and there were more than two thousand of them - and neither then nor afterwards could anyone say how they died. Aristotle specifically dwells on the fact that the ephors, taking power, first of all declared war on the helots in order to legitimize the murder of the latter. In general, the Spartans treated them rudely and cruelly. They forced the helots to drink unmixed wine, and then brought them to common meals to show the youth what intoxication is. They were ordered to sing cheesy songs and dance ridiculous dances, forbidding the entertainments befitting a free man. Even much later, during the campaign of the Thebans in Laconia, when the captured helots were ordered to sing something from Terpander, Alkman, or the Laconian Spendont, they refused, because the gentlemen did not like it. So, whoever says that in Lacedaemon the free man is free to the end, and the slave is completely enslaved, he correctly identified the current state of affairs. But, in my opinion, all these strictnesses appeared among the Spartans only later, namely, after a great earthquake, when, as they say, the helots, having set out together with the Messenians, terribly outraged throughout Laconia and almost destroyed the city. I, at least, cannot attribute such a vile deed as cryptia to Lycurgus, having formed an idea of \u200b\u200bthe character of this man from that meekness and justice, which otherwise mark his whole life and are confirmed by the testimony of a deity.

29. When the most important of the laws took root in the customs of the Spartans and the political system was strong enough to continue to be maintained by its own forces, then, like the god of Plato, who rejoiced at the sight of the emerging universe, which first set in motion, Lycurgus was delighted and delighted with the beauty and grandeur of his legislation, launched in the course and already coming in his own way, and wished to ensure him immortality, inviolability in the future - since this is accessible to human understanding. So, having gathered the National Assembly, he declared that now everything has been given the proper measure, that what has been done is enough for the prosperity and glory of the state, but there remains one more question, the most important and basic, the essence of which he will reveal to his fellow citizens only after he asks God for advice. . Let them strictly adhere to the published laws and do not change anything in them until he returns from Delphi, but when he returns, he will do what God commands. Everyone agreed and asked him to leave as soon as possible, and, having taken an oath from the kings and elders, and then from other citizens that, until Lycurgus returned, they would remain faithful to the existing system, he left for Delphi. Having arrived at the oracle and made a sacrifice to God, Lycurgus asked if his laws were good and sufficient to lead the city to prosperity and moral perfection. God answered that the laws were good, and the city would be at the height of its glory if it did not change the Lycurgus system. Having written down the prophecy, Lycurgus sent it to Sparta, and he himself, again sacrificing to God and saying goodbye to his friends and son, decided not to release his fellow citizens from their oath and to die voluntarily for this: he had reached the age when you can still continue life, but you can also to leave her, especially since all his plans came, apparently, to a happy conclusion. He starved himself to death, firmly believing that even the death of a statesman should not be useless for the state, that his very death should not be a weak-willed submission, but a moral deed. For him, he reasoned, after the most beautiful deeds that he accomplished, this death will truly be the crown of good luck and happiness, and for fellow citizens who have sworn to remain faithful to his institutions until he returns, it will be the guardian of those blessings that he delivered to them during his lifetime. And Lycurgus was not mistaken in his calculations. Sparta excelled all Greek cities in goodness and glory for five hundred years, while observing the laws of Lycurgus, in which none of the fourteen kings who ruled after him, up to Agida, the son of Archidamus, changed anything. The creation of the post of ephors served not to weaken, but to strengthen the state: it was only at first glance a concession to the people, but in fact it strengthened the aristocracy.

30. In the reign of Agida, the coin first penetrated Sparta, and with it greed and money-grubbing returned, and all through the fault of Lysander. Personally, he was inaccessible to the power of money, but he filled the fatherland with a passion for wealth and infected with luxury, bringing - bypassing the laws of Lycurgus - gold and silver from the war. Before, however, when these laws remained in force, Sparta led the life not of an ordinary city, but rather of a highly experienced and wise husband, or, more precisely, like Hercules in the songs of poets goes around the universe with only a club and a skin on his shoulders, punishing unjust and bloodthirsty tyrants, in the same way, Lacedaemon, with the help of a wandering stick and a simple cloak, dominated Greece, voluntarily and willingly obeying him, overthrew lawless and tyrannical power, resolved disputes between the belligerents, calmed the rebels, often without even moving his shield, but sending one the only ambassador, whose orders everyone immediately obeyed, like bees, when the queen appears, they gather in unison and each takes its place. Such were the prosperity and justice that flourished in the city.

All the more, some writers amaze me, claiming that the Spartans perfectly carried out orders, but they themselves did not know how to order, and referring with approval to King Theopompus, who, in response to someone’s words, that de Sparta is kept by the firm power of kings, said: “ No, or rather, the obedience of citizens. People do not long obey those who cannot rule, and obedience is an art taught by a ruler. Whoever leads well, they follow well, and just as the skill of a horse tamer is to make a horse meek and meek, so the king’s task is to inspire humility, while the Lacedaemonians inspired the rest not only humility, but also a desire to obey. Well, yes, because they were asked not for ships, not for money, not for hoplites, but only for a Spartan commander and, having received, they met him with respect and fear, like the Sicilians of Gylippus, the inhabitants of Chalkis - Brasida, and the entire Greek population of Asia - Lysander, Kallikratida and Agesilaus. These commanders were called the rulers and mentors of the peoples and authorities of the whole earth, and the state of the Spartans was looked upon as an uncle, a teacher of a decent life and wise administration. This, apparently, is jokingly hinted at by Stratonicus, proposing a law according to which the Athenians are charged with the duty of celebrating the sacraments and organizing processions, the Eleans - to be judges at the games, since in these studies they know no equal, and if one or the other in what guilty - flog the Lacedaemonians. But this, of course, is a mischievous mockery, nothing more. But Aeschines, a follower of Socrates, seeing how the Thebans boast and boast of their victory at Leuctra, noticed that they are no different from the boys who rejoice, puffing up their uncle.

31. However, this was not the main goal of Lycurgus - he did not at all strive to put his city at the head of a huge number of others, but, believing that the well-being of both an individual and an entire state is a consequence of moral height and internal harmony, he directed everything towards the Spartans remained free as long as possible, independent and prudent. On the same foundations, Plato, Diogenes, Zeno, and in general everyone who spoke about this and whose works gained praise built their state. But after them, only writings and speeches remained, and Lycurgus, not in writings and not in speeches, but in fact, created a state that had no equal and no, showing the eyes of those who do not believe in the existence of a true sage, a whole city, devoted to philosophy. It is quite understandable that he surpasses in glory all the Greeks who have ever acted in the public arena. That is why Aristotle claims that Lycurgus did not receive in Lacedaemon everything that is due to him by right, although the honors rendered by the Spartans to their legislator are extremely great: a temple was erected to him and sacrifices are made annually, as to a god. It is said that when the remains of Lycurgus were transferred to their homeland, lightning struck the tomb. Subsequently, this did not fall to the lot of any of the famous people, except for Euripides, who died and was buried in Macedonia near Aretusa. With him alone, after death, the same thing happened that once - with the purest and most amiable man to the gods, and in the eyes of the passionate admirers of Euripides - this is a great sign that serves as a justification for their ardent commitment.

Lycurgus died, according to some writers, in Kirra, Apollothemis reports that shortly before his death he arrived in Elis, Timaeus and Aristoxenus - that the last days of his life were spent in Crete; Aristoxenus writes that the Cretans even show his tomb near Pergamon by the high road.

He left, they say, the only son named Antior, who died childless, and the line of Lycurgus ceased. But friends and relatives, in order to continue his labors, established a society that existed for a long time, and the days on which they met were called Lycurgides. An aristocrat, the son of Hipparchus, says that when Lycurgus died in Crete, those who received him at home burned the body and scattered the ashes over the sea; such was his request, for he feared that if his remains were transported to Lacedaemon, they would not say that, they say, Lycurgus had returned and the oath had lost its force, and under this pretext they would not make changes to the system he created.

This word means “agreement”, as well as “saying of the oracle”.).... - The chant, under which the Spartans went into battle, is also mentioned by Xenophon (Numa, 12 Lys., 19. Sparta was the only state in Greece that cared about preserving military secrets.

Periodization of state-legal development Ancient Greece.

Lecture 3. The evolution of statehood in Ancient Greece

Questions:

1. Periodization of the state-legal development of Ancient Greece.

Greek polis.

2. The evolution of the ancient Athenian state.

3. Social and state structure of Ancient Sparta.

Ancient Greece, or rather Hellas, occupied a vast territory that covered the south of the Balkan Peninsula, the islands of the Aegean Sea, the coast of Thrace, the western coastal strip of Asia Minor, southern Italy and part of Sicily. The Greeks themselves called themselves Hellenes in honor of their deity Hellenes, and the Romans later called them Greeks.

At the end of the III millennium BC. Greece was conquered by the Achaean tribes. The Mycenaean kingdom became the first state association of various tribes and clans. The presence of centralized power, concentrated in the hands of the leader, one system taxation and administrative division resembled the organization of power of the ancient Eastern proto-states. However, under the onslaught of new (Dorian) conquests, Mycenaean civilization fell.

The process of the subsequent emergence of ancient states had a very important feature. Plutarch, the famous ancient Greek historian (1st century AD), in his Comparative Biographies, believed that the founding father of Sparta was the mythical Lycurgus, who became king by retra, i.e. by oral agreement between the Spartans and the deities. The same founder of Athens, according to Plutarch, was the god-man - Theseus (the son of an earthly woman and the god Poseidon, who gave him divine power), who performed a lot of supernatural feats. Thus, Plutarch considered the supernatural origin of the ancient states an obvious fact. When studying ancient statehood, this circumstance must be taken into account. Historical figures are often replaced by legendary ones, and their versions are offered instead of substantiated facts.

In science, the division of the post-Mycenaean stage of ancient Greek statehood into three main periods is common:

Homeric period - XI-IX centuries. BC.;

Archaic period - VIII-VI centuries. BC.;

Classical period - V-V centuries. BC.

The Homeric period (XI-IX centuries BC) is characterized by the dominance of tribal relations, when in the traditional sense there was no state structure yet and primitive military democracy prevailed. By the end of this period, tribal relations finally disintegrate, and the slave system comes to replace the tribal system.

In the archaic period, a strong Athenian state was created, which will be discussed below.

During the classical period, the ancient Greek slave-owning society and the polis system flourished. In the 5th century BC. Greece defended its independence in the Greco-Persian wars (500-449 BC). A great contribution to the victory over the Persians was made by the unification of the Greek policies (Athens, Corinth, and many others) into the Delian Maritime Union under the leadership of Athens. Therefore, the union actually turned into an Athenian maritime power - arche, which some scholars characterize as a kind of ancient confederation. The Peace of Callia was concluded in 449 BC. He became victorious for the Greeks and ended the Greco-Persian wars. Thus, the first Athenian Maritime Union fulfilled its military-political task.

The second Athenian maritime alliance was created in 378 BC. with the aim of confronting the Peloponnesian Union, led by Sparta. The Peloponnesian Union was a grouping of Greek policies in which the oligarchic order prevailed, and the aristocracy dominated. After the defeat in the Peloponnesian War, Athens forever lost its leading role in the history of ancient Greece.

Note that the largest ancient Greek city-states mentioned: Athens, Sparta, Corinth - existed in the form of a polis and were a city with adjacent rural areas. For the history of the state and law, two policies - Athens and Sparta - are of the greatest interest as the most prominent representatives of the two state-legal "models". Classical Athens was dominated by a democratic regime, while Sparta was dominated by an oligarchic one.

What was the “polis” as a universal type of the emerging statehood of the Dorians, and what was the status of the community members? Policy, according to Aristotle, was the end result of the development of the family, the village, their unification. The polis was a small closed territory with a relatively small population. It had an institution of citizenship, giving the right to a land plot within the city limits. In addition, in any policy there were self-government bodies - people's assemblies and elected magistracies.

As the core of classical civilization and part of the civil community, the ancient Greek policy had its own characteristics and properties. Its economic basis was the unity of the city and the villages adjacent to it. In the period of formation, the policy was formed from territorial communities; the center was a settlement, a temple, a sanctuary, where a fortress was often located. Near it was a market - a place of trade, artisans lived there. Gradually, this urban settlement turned into an administrative center. The inhabitants of the policy called themselves by the name of this center. The upper part of the city was called the acropolis.

In that era, any of the states of Hellas was small sizes. The population of the policy was small; rarely exceeded ten thousand people. The polis could survive only with a small population and a limited territory, and the excessive birth rate was not approved by the authorities. From the walls of the city fortress, one could look at almost the entire state, and the citizens of the policy knew everyone by sight. Formally, the policy was a kind of socio-political union of all citizens, regardless of their social and financial status. In fact, inside him there was a fierce struggle between the demos and the eupatrides.

An important function of the policy is to maintain civil peace within the community. Therefore, the policy is also a kind of political and legal association, whose citizens participate in the legislative and judicial power. A full member of such a policy considered himself responsible for all the affairs of the civil community, was a socially active patriot of his city-state. He was obliged to serve in the militia, to protect the common cause of the policy. The main force of the militia were those who sat in the people's assembly. The coincidence of political and military organization was a peculiar form in which the process of formation of the slave-owning state took place. Wealthy citizens also carried material duties, arranging a liturgy at their own expense.

As mentioned, all citizens of the policy, represented by heads of families, had the right to a piece of land (claire), and in principle, its size was equal for everyone. Private ownership of land in Greece was known as early as the time of Homer. Land was divided into two categories: polis (communal) and private. The ancient form of landed property appears in a peculiar dual form:

a) as the property of the policy (therefore, only a citizen of this policy can sell or donate land) and at the same time

b) as private property.

The policy forbade strangers and foreigners any kind of transactions with landed property. In addition, the community followed the transactions of citizens regarding land allotments, approved the land maximum, controlled the fairness and validity of receiving land by inheritance, and in the absence of heirs, took escheat lands to its fund, etc. The loss of a plot of land undermined the social prestige of the community member. Nevertheless, the customs and traditions of the policy did not prevent noble aristocrats from enslaving community-peasants and appropriate their plots of land. At the same time, it must be taken into account that the debtor's self-mortgage did not become common in Attica, and Solon's reforms in the 6th century. BC. generally banned. Public consciousness condemned poverty, the ruin of their fellow citizens, as well as excessive enrichment. In case of need, a community member could count on the support of fellow tribesmen. The stability of the policy was achieved by establishing a maximum land allotment, restrictions on the purchase and sale of land, and additional taxation of wealthy citizens. These measures were intended to prevent the weakening of the cohesion of the civil collective; maintain a layer of free producers - owners. Small and medium peasants were the main social support of the policy. On the other hand, wealthy citizens had priority in many positions in the policy.

So, the presence of a land allotment, and later - a certain income from land plot was the main condition for a citizen to have not only military, but also political and civil rights. These included:

the right to participate in the work of the people's assembly;

to elect officials and supervise their activities;

· to be called to the administration of justice.

Outwardly, the polis seemed to be an almost ideal community of equal people, but a careful analysis revealed that the polis is not just a large community, but a very stable political and social organism that served as the basis of ancient society. Otherwise, it is difficult to understand the reason for its survivability for many centuries.

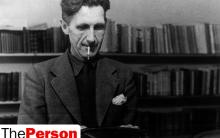

PLUTARCH(c. 46 - c. 120), ancient Greek writer and historian. The main work is "Comparative Lives" of prominent Greeks and Romans (50 biographies). The rest of the numerous works that have come down to us are united under the conditional name "Moralia".

PLUTARCH(c. 46 - c. 120), ancient Greek writer, author of moral-philosophical and historical-biographical works. From the huge literary heritage of Plutarch, which amounted to approx. 250 compositions, no more than a third of the works have survived, most of which are united under the general name "Moral". Another group - "Comparative Lives" - includes 23 pairs of biographies of prominent statesmen of ancient Greece and Rome, selected according to the similarity of their historical mission and the similarity of characters.

Biography

The ancient tradition did not preserve the biography of Plutarch, but it can be reconstructed with sufficient completeness from his own writings. Plutarch was born in the 40s of the 1st century in Boeotia, in the small town of Chaeronea, where in 338 BC. e. there was a battle between the troops of Philip of Macedon and the Greek troops. In the time of Plutarch, his homeland was part of the Roman province of Achaia, and only the carefully preserved traditions of antiquity could testify to its former greatness. Plutarch came from an old wealthy family and received a traditional grammatical and rhetorical education, which he continued in Athens, becoming a student at the school of the philosopher Ammonius. Returning to his native city, from his youthful years he took part in its administration, holding various magistracies, including the prominent position of eponymous archon. Plutarch repeatedly went on political assignments to Rome, where he struck up friendly relations with many statesmen, among whom was a friend of Emperor Trajan, the consul Quintus Sosius Senekion; Plutarch dedicated his "Comparative Biographies" and "Table Talks" to him. Proximity to influential circles of the empire and growing literary fame brought Plutarch new honorary positions: under Trajan (98-117) he became proconsul, under Hadrian (117-138) - procurator of the province of Achaia. A surviving inscription from the era of Hadrian testifies that the emperor granted Plutarch Roman citizenship, classifying him as a member of the Mestrian family.

Despite a brilliant political career, Plutarch chose a quiet life in his native city, surrounded by his children and students, who made up a small academy in Chaeronea. "As for me," Plutarch points out, "I live in small town and so that it does not become even smaller, I willingly remain in it.

Plutarch's public activities earned him great respect in Greece. Around the year 95, fellow citizens elected him a member of the college of priests of the sanctuary of Delphic Apollo. A statue was erected in his honor at Delphi, from which, during excavations in 1877, a pedestal with a poetic dedication was found.

Plutarch's lifetime refers to the era of the "Hellenic renaissance" of the early 2nd century. During this period, the educated circles of the Empire were seized by the desire to imitate the ancient Hellenes as in the customs Everyday life as well as in literary work. The policy of Emperor Hadrian, who provided assistance to the Greek cities that had fallen into decay, could not but arouse among Plutarch's compatriots the hope of a possible revival of the traditions of the independent policies of Hellas.

The literary activity of Plutarch was primarily of an educational and educational character. His works are addressed to a wide range of readers and have a pronounced moral and ethical orientation associated with the traditions of the teaching genre - diatribe. Plutarch's worldview is harmonious and clear: he believes in a higher mind that governs the universe, and is like a wise teacher who never tires of reminding his listeners of eternal human values.

Small works

The wide range of topics covered in Plutarch's writings reflects the encyclopedic nature of his knowledge. He creates "Political Instructions", essays on practical morality ("On envy and hatred", "How to distinguish a flatterer from a friend", "On love for children", etc.), he is interested in the influence of literature on a person ("How young men get to know poetry") and questions of cosmogony ("On the generation of the world soul according to Timaeus").

The works of Plutarch are imbued with the spirit of Platonic philosophy; his writings are full of quotations and reminiscences from the works of the great philosopher, and the treatise "Platonic Questions" is a real commentary on his texts. Plutarch is concerned about the problems of religious and philosophical content, to which the so-called. Pythian dialogues ("On the sign "E" in Delphi", "On the decline of the oracles"), the essay "On the daimonia of Socrates" and the treatise "On Isis and Osiris".

A group of dialogues clothed in traditional form conversations of companions at a feast, is a collection of entertaining information from mythology, deep philosophical remarks and sometimes curious natural science ideas. The titles of the dialogues can give an idea of the variety of questions Plutarch is interested in: "Why do we not believe autumn dreams"," Which hand of Aphrodite was wounded by Diomedes", "Various legends about the number of Muses", "What is the meaning of Plato in the conviction that God always remains a geometer", etc.

To the same circle of Plutarch's works belong "Greek questions" and "Roman questions", containing different points of view on the origin of state institutions, traditions and customs of antiquity.

"Comparative Lives"

The main work of Plutarch, which became one of the most famous works of ancient literature, was his biographical writings.

"Comparative Lives" absorbed a huge historical material, including information from the works of ancient historians that have not survived to this day, the author's personal impressions of ancient monuments, quotations from Homer, epigrams and epitaphs. It is customary to reproach Plutarch for an uncritical attitude to the sources used, but it must be borne in mind that the main thing for him was not the historical event, but the trace left by him in history.

This can be confirmed by the treatise "On the Malice of Herodotus", in which Plutarch reproaches Herodotus for partiality and distortion of the history of the Greco-Persian wars. Plutarch, who lived 400 years later, in an era when, in his words, a Roman boot was raised over the head of every Greek, wanted to see the great generals and politicians not as they really were, but the ideal embodiment of valor and courage. He did not seek to recreate history in all its real fullness, but found in it outstanding examples of wisdom, heroism, self-sacrifice for the sake of the motherland, designed to strike the imagination of his contemporaries.

In the introduction to the biography of Alexander the Great, Plutarch formulates the principle that he put as the basis for the selection of facts: “We do not write history, but biographies, and virtue or depravity is not always visible in the most glorious deeds, but often some insignificant deed, word or joke better reveal the character of a person than battles in which tens of thousands die, the leadership of huge armies and the siege of cities.

The artistic skill of Plutarch made "Comparative Lives" a favorite reading for young people who learned from his writings about the events of the history of Greece and Rome. The heroes of Plutarch became the personification of historical eras: ancient times were associated with the activities of the wise legislators Solon, Lycurgus and Numa, and the end of the Roman Republic seemed to be a majestic drama driven by the clashes of the characters of Caesar, Pompey, Crassus, Antony, Brutus.

It can be said without exaggeration that thanks to Plutarch, European culture developed an idea of ancient history as a semi-legendary era of freedom and civic prowess. That is why his works were highly valued by the thinkers of the Enlightenment, the figures of the Great French Revolution and the generation of the Decembrists.

The very name of the Greek writer became a household name, since "Plutarchs" in the 19th century called numerous publications of biographies of great people.

“I don’t need a friend who, agreeing with me in everything, changes his views with me, nodding his head, because the shadow does the same better.”

These words belong to the famous ancient Greek biographer, philosopher, historian Plutarch. They allow us to understand why the name and works of this truly unique and interesting person are known to this day. Although the facts of the biography of Plutarch are largely lost, some information is still available thanks to Plutarch himself. In his own writings, he mentioned certain events that took place on his life path.

Childhood of Plutarch

Plutarch was born in 46 in the Greek city of Chaeronea in Boeotia. Thanks to his parents, the future philosopher received an excellent education, which formed the basis of his future activities. Family upbringing has big influence on his worldview, helped Plutarch to comprehend many knowledge, and later become the author of numerous works.

His father Autobulus and grandfather Lamprius were well educated and smart people. They told him interesting historical facts, about famous personalities, could keep up the conversation on any topic. The education of his father and grandfather allowed Plutarch to receive his primary education at home.

He had two more brothers - also enlightened people. It is known that despite the education of all family members, they were not aristocrats, although they were wealthy citizens. All this made their family very respected among those around them.

Youth of Plutarch

From the earliest years, Plutarch was constantly studying and, by the way, did this all his life. To receive a special education, he went to Athens, where he studied such sciences as rhetoric, mathematics, philosophy and others. His main teacher in those years was Ammonius, who played a significant role in shaping Plutarch's philosophical views.

Plutarch's activities

After receiving his education, Plutarch returns to his hometown and devotes the rest of his life to the service of Chaeronea. Thanks to his versatile knowledge, he has been working in managerial positions since his youth. By the nature of his activities, he often had to visit the Roman emperor Trajan himself in order to resolve certain political issues.

During business visits to Rome, he still managed to attend philosophical and historical lectures, and actively spoke at them himself. During such conversations, he became friends with the consul Quintus Sosius Senekion, Trajan's best friend. This friendship with Senekion, coupled with Plutarch's growing fame, served to advance him in his career. Until 117, he served as consul, and after the death of Trajan, under the new Roman emperor Adrian, Plutarch served as procurator of the province of Achaia.

These positions were very responsible and important. To understand their full significance, it should be noted that not a single decision in the province of Achaia could be valid without the participation of Plutarch. This means that any event had to be coordinated with it. This or that decision was carried out only if it was approved by Plutarch.

In addition to politics, he paid great attention to religion and social activities. So, around the year 95, Plutarch was elected priest in the temple of Apollo at Delphi. The priests at that time were chosen by society, and this fact testifies to the deep respect and veneration of Plutarch among the people. People even erected a statue in honor of him.

Works of Plutarch

Plutarch left behind many significant works. He wrote more than two hundred essays on a variety of topics. Mostly, they were historical and instructive in nature. Unfortunately, only a small part of his works have survived to our century. Among them is his main work - "Comparative Biographies", where he described the biographies of famous people: Romans and Greeks.

The essence of "Comparative Lives" is that the author took the biographies of two personalities and made comparisons. So, in this work one can find descriptions of the life of Alexander the Great, Gaius Julius Caesar, Theseus, Romulus, Cicero and others. This work is of great importance for us, as it contains reliable and most complete information about ancient personalities. The biographies of twenty-two couples have survived to this day, the rest have been lost.

Among the other works of Plutarch: "Political Instructions", "On the Ingenuity of Animals", "On the Love of Children", "On Talkativeness", "On the Malice of Herodotus", "On Excessive Curiosity" and many others on a wide variety of topics. Of great interest are the Pythian dialogues, where he discusses various religious and philosophical issues of his time.

Plutarch's Disciples

Despite the fact that he was a very influential politician and was active in public life, Plutarch was also a good family man and father to his children. It is not known for certain how many children he had. Some sources mention five sons.

Like Plutarch's father, he taught his children himself. His house was never empty. Young people have always been welcome here. In this regard, Plutarch opened his own Academy, where he was a leader and lecturer. Thus, he had many students, but history, unfortunately, does not mention their names. It is only known that one of the followers of Plutarch is his nephew Sextus of Chaeronea, who raised Marcus Aurelius himself, the famous future emperor.

Plutarch died in 127. He lived for eighty-one years. For that time it was a very respectable age, few managed to live up to such years. He always adhered to a healthy lifestyle and constantly warned his loved ones and all people in general with the words: "No body can be so strong that wine could not damage it." Indeed, the "golden" words, which through many centuries have not lost their relevance.

Plutarch Plutarch

(c. 45 - c. 127), ancient Greek writer and historian. The main work is "Comparative Lives" of prominent Greeks and Romans (50 biographies). The rest of the numerous works that have come down to us are united under the conditional name "Moralia".

PLUTARCHPLUTARCH (c. 46 - c. 120), ancient Greek writer, historian, author of moral-philosophical and historical-biographical works. From the huge literary heritage of Plutarch, which amounted to approx. 250 compositions, no more than a third of the works have survived, most of which are united under the general title "Moral". Another group - "Comparative Lives" - includes 23 pairs of biographies of prominent statesmen of Ancient Greece and Rome, selected according to the similarity of their historical mission and similarity of characters.

Biography

The ancient tradition did not preserve the biography of Plutarch, but it can be reconstructed with sufficient completeness from his own writings. Plutarch was born in the 40s of the 1st century in Boeotia, in the small town of Chaeronea, where in 338 BC. e. there was a battle between the troops of Philip of Macedon and the Greek troops. In the time of Plutarch, his homeland was part of the Roman province of Achaia, and only the carefully preserved traditions of antiquity could testify to its former greatness. Plutarch came from an old wealthy family and received a traditional grammatical and rhetorical education, which he continued in Athens, becoming a student at the school of the philosopher Ammonius. Returning to his native city, from his youthful years he took part in its administration, holding various magistracies, including the prominent position of archon-eponym (cm. EPONYMS).

Plutarch repeatedly went on political assignments to Rome, where he struck up friendly relations with many statesmen, among whom was a friend of Emperor Trajan, the consul Quintus Sosius Senekion; Plutarch dedicated Comparative Biographies and Table Talk to him. Proximity to influential circles of the empire and growing literary fame brought Plutarch new honorary positions: under Trajan (98-117) he became proconsul, under Hadrian (117-138) - procurator of the province of Achaia. A surviving inscription from the era of Hadrian testifies that the emperor granted Plutarch Roman citizenship, classifying him as a member of the Mestrian family.

Despite a brilliant political career, Plutarch chose a quiet life in his native city, surrounded by his children and students, who made up a small academy in Chaeronea. “As for me,” Plutarch points out, “I live in a small town and, so that it does not become even smaller, I willingly stay in it.” Plutarch's public activities earned him great respect in Greece. Around the year 95, fellow citizens elected him a member of the college of priests of the sanctuary of Delphic Apollo. A statue was erected in his honor at Delphi, from which, during excavations in 1877, a pedestal with a poetic dedication was found.

The time of Plutarch's life refers to the era of the "Hellenic revival" of the beginning of the 2nd century. During this period, the educated circles of the Empire were seized by the desire to imitate the ancient Hellenes both in the customs of everyday life and in literary creativity. The policy of Emperor Hadrian, who provided assistance to the Greek cities that had fallen into decay, could not but arouse among Plutarch's compatriots the hope of a possible revival of the traditions of the independent policies of Hellas.

The literary activity of Plutarch was primarily of an educational and educational character. His works are addressed to a wide range of readers and have a pronounced moral and ethical orientation associated with the traditions of the teaching genre - diatribe. (cm. DIATRIBE). Plutarch's worldview is harmonious and clear: he believes in a higher mind that governs the universe, and is like a wise teacher who never tires of reminding his listeners of eternal human values.

Small works

The wide range of topics covered in Plutarch's writings reflects the encyclopedic nature of his knowledge. He creates “Political Instructions”, essays on practical morality (“On envy and hatred”, “How to distinguish a flatterer from a friend”, “On love for children”, etc.), he is interested in the influence of literature on a person (“How young men get to know poetry") and questions of cosmogony ("On the generation of the world soul according to Timaeus").

The works of Plutarch are imbued with the spirit of Platonic philosophy; his writings are full of quotations and reminiscences from the works of the great philosopher, and the treatise Platonic Questions is a real commentary on his texts. Plutarch is concerned about the problems of religious and philosophical content, to which the so-called. Pythian dialogues (“On the sign “E” in Delphi”, “On the decline of the oracles”), the essay “On the daimonia of Socrates” and the treatise “On Isis and Osiris”.

The group of dialogues, dressed in the traditional form of conversations of companions at a feast, is a collection of entertaining information from mythology, deep philosophical remarks and sometimes curious natural science ideas. The titles of the dialogues can give an idea of the variety of questions Plutarch is interested in: “Why do we not believe in autumn dreams”, “Which hand of Aphrodite was hurt by Diomedes”, “Various legends about the number of Muses”, “What is the meaning of Plato in the belief that God always remains a geometer” . To the same circle of Plutarch's works belong "Greek Questions" and "Roman Questions", containing different points of view on the origin of state institutions, traditions and customs of antiquity.

Comparative biographies

The main work of Plutarch, which became one of the most famous works of ancient literature, was his biographical writings. "Comparative Lives" absorbed a huge historical material, including information from the works of ancient historians that have not survived to this day, the author's personal impressions of ancient monuments, quotations from Homer, epigrams and epitaphs. It is customary to reproach Plutarch for an uncritical attitude to the sources used, but it must be borne in mind that the main thing for him was not the historical event itself, but the trace it left in history.

This can be confirmed by the treatise "On the Malice of Herodotus", in which Plutarch reproaches Herodotus for partiality and distortion of the history of the Greco-Persian wars. (cm. GRECO-PERSIAN WARS). Plutarch, who lived 400 years later, in an era when, in his words, a Roman boot was raised over the head of every Greek, wanted to see the great generals and politicians not as they really were, but the ideal embodiment of valor and courage. He did not seek to recreate history in all its real fullness, but found in it outstanding examples of wisdom, heroism, self-sacrifice for the sake of the motherland, designed to strike the imagination of his contemporaries.

In the introduction to the biography of Alexander the Great, Plutarch formulates the principle that he put as the basis for the selection of facts: “We do not write history, but biographies, and virtue or depravity is not always visible in the most glorious deeds, but often some insignificant deed, word or joke better reveal the character of a person than battles in which tens of thousands die, the leadership of huge armies and the siege of cities. The artistic skill of Plutarch made the "Comparative Lives" a favorite reading for young people who learned from his writings about the events of the history of Greece and Rome. The heroes of Plutarch became the personification of historical eras: ancient times were associated with the activities of the wise legislators of Solon (cm. SOLON), Lycurgus (cm. LYCURGUS) and Numa (cm. NUMA POMPILIUS), and the end of the Roman Republic was presented as a majestic drama, driven by the clashes of the characters of Caesar (cm. CAESAR Gaius Julius), Pompeii (cm. POMPEI Gnaeus), Krassa (cm. KRASS), Anthony, Brutus (cm. Brutus Decimus Junius Albinus).

It can be said without exaggeration that thanks to Plutarch, European culture developed an idea of ancient history as a semi-legendary era of freedom and civic prowess. That is why his works were highly valued by the thinkers of the Enlightenment, the figures of the Great French Revolution and the generation of the Decembrists. The very name of the Greek writer became a household name, since in the 19th century numerous publications of biographies of great people were called "Plutarchs".

encyclopedic Dictionary . 2009 .

See what "Plutarch" is in other dictionaries:

From Chaeronea (c. 45 c. 127), Greek. writer and philosopher. Belonged to the Platonic Academy and professed the cult of Plato, paying tribute to numerous. stoich., peri pathetic. and Pythagorean influences in the spirit characteristic of that time ... ... Philosophical Encyclopedia

- (c. 40 120 AD) Greek writer, historian and philosopher; lived in the era of stabilization of the Roman Empire, when the economy, political life and the ideology of ancient society entered a period of prolonged stagnation and decay. Ideological ... ... Literary Encyclopedia

- (c. 46 c. 127) philosopher, writer and historian, from Chaeronea (Boeotia) The highest wisdom when philosophizing, not seeming philosophizing and a joke to achieve a serious goal. Conversation should be as common to those who feast as wine. Chief... ... Consolidated encyclopedia of aphorisms

Plutarch- Plutarch. Plutarch (c. 45 c. 127), Greek writer. The main work "Comparative Lives" of prominent Greeks and Romans (50 biographies). The rest of the numerous works that have come down to us are united under the conditional name "Moralia" ... Illustrated Encyclopedic Dictionary

And husband. Star. redk.Otch.: Plutarchovich, Plutarchovna. Derivatives: Tarya; Arya. Origin: (Greek personal name Plutarchos. From plutos wealth and arche power.) Dictionary of personal names. Plutarch a, m. Star. rare Reporter: Plutarchovich, Plutarkhovna. Derivatives… Dictionary of personal names

Plutarch, Plutarchos, from Chaeronea, before 50 after 120 n. e., Greek philosopher and biographer. He came from a wealthy family living in a small town in Boeotia. In Athens, he studied mathematics, rhetoric and philosophy, the latter mainly from ... ... Ancient writers

PLUTARCH Dictionary-reference book on Ancient Greece and Rome, on mythology

PLUTARCH- (c. 46 - c. 126) Greek essayist and biographer, born in Chaeronea (Boeotia), studied in Athens, was a priest of the Pythian Apollo in Delphi, traveled to Egypt, Italy, lived in Rome. Most of the works of Plutarch devoted to scientific, ... ... List of ancient Greek names

- (c. 45 c. 127) ancient Greek writer and historian. Main work Comparative biographies of prominent Greeks and Romans (50 biographies). The rest of the numerous works that have come down to us are united under the conditional name of Moralia ... Big Encyclopedic Dictionary

- (Plutarchus, Πλούταρχος). A Greek writer who lived in Boeotia in the first century A.D., who traveled widely and spent some time in Rome. He died about 120 tons from R. X. Of his works of historical and philosophical content, the most remarkable ... ... Encyclopedia of mythology

Chicken in kefir - recipes for marinated, stewed and baked poultry for every taste!

Simple Chicken Recipe in English (Fried) Recipes in English with translation

Chicken hearts with potatoes: cooking recipes How to cook delicious chicken hearts with potatoes

Recipes for dough and fillings for jellied pies with mushrooms

Stuffed eggplant with chicken and mushrooms baked in the oven with cheese crust Cooking eggplant stuffed with chicken